Use of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.

Do you know where the octave pairs are on your kalimba?

The octave is the most fundamental interval in essentially any music. Octave harmonies are not rich, but they are powerful. If your kalimba has eight notes or more, you likely have one or maybe even several octave pairs. Learning which note pairs are an octave apart, as well as how to use the octaves in playing, are essential to becoming a good kalimba player.

In the simplest of terms, an octave is the interval between two notes at the opposite end of a major scale. Sing “DO re mi fa so la ti DO” – the interval from the low DO to the high DO is one octave. These two notes an octave apart have the same name and they sound the same to us, even though one is high and the other is low.

One simple way to put an octave interval firmly in your mind is for you to sing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.” The song starts out low on “Some” and jumps up exactly one octave to “where.” The two notes, separated by an octave, somehow seem the same. Harmonically, they are the same. Melodically, the notes of any octave pair (8 notes apart) have the same name – “C” or “D” for example, (or whatever key you started singing in).

From a physics point of view, an octave is an interval between two notes that have frequencies that differ by a factor of 2. Double the frequency and you go up an octave. If you play an “A 440 Hz ” (that is, an A at 440 vibrations per second), doubling the frequency to 880 Hz will make another A note that is an octave higher.

Hmm…that definition of an octave (while precise) is probably not particularly helpful to most people. Let me try again. Have you ever been in a group of people who all sang the same melody? Some people are smaller, and they have small resonating vocal cavities, and they sing with higher voices. Other people have larger vocal cavities, and they sing with lower voices. They are all singing the same melody – but the larger people (usually men) are singing an octave lower than the smaller people (usually women or children). An operatic soprano might even sing an octave higher than the other women, or a bass singer might sing another octave below the other men.

Singing octaves is completely different from singing part harmonies, where the parts are complementary but not necessarily separated by octaves. What we are talking about here is when people all know the song and its melody, and sing the same thing. Each person’s voice will be most comfortable somewhere, lower or higher, and they are all singing the same note…or that note at least one octave higher or lower.

If two notes that are an octave apart are sung or played simultaneously, they sound great together.

The piano has a range of just over seven octaves, and the same melody can be played in each of those octaves.

The entire hearing range of a young human is between 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz – or about 10 full octaves. (Hz = Hertz, a unit of frequency.) As they age, humans lose hearing range from the top (highest frequency) down. At age 55, I cannot hear anything above 12,000 Hz, which means I am now missing almost an entire octave at the top.

Most people’s singing voices have a range of more than one octave, but less than two. Studied singers can have larger vocal ranges. Most horns or flutes have a range of a bit more than two octaves. Guitars have a range of almost four octaves.

The range of small kalimbas is one octave; mbiras have a three-octave range, but most kalimbas have a range of about two octaves.

In general, instruments with larger ranges can play fuller, more complex music and instruments with smaller ranges play simpler music.

Octave intervals are fundamental in essentially all music. Octave intervals are found not just in modern music or western music, but in all primitive music and in essentially all world music as well. The ability to recognize octaves is related to being human.

Yes, that is right – it doesn’t matter if you are Beethoven or Bach, or an ancestral player of the mbira or the karimba – each of these musicians knew how to use octaves on their instruments of choice.

Beethoven and Bach had it simple: on their keyboards, the octave interval is defined by the distance from one C to the next higher C. Once your hand knows that spacing – usually played with the thumb and the pinky finger on the same hand, stretched but not stretched to the max – you can shift your hand up or down the keyboard to make other octave pairs.

The notes on an mbira or kalimba are not so orderly as the notes on a keyboard, and octaves on these instruments could be difficult to play… except that the creators of these instruments often went out of their way to make some of the octaves quite easy to play, even easier than on the piano keyboard.

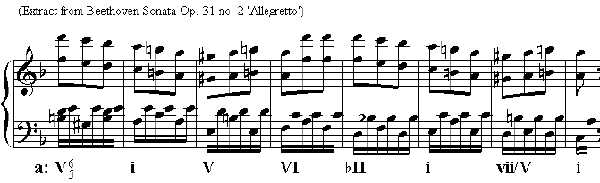

Beethoven made his music strong by playing the same melody in several different octaves – the bass violins, the cellos, the violas, the violins, the flutes. Of course, other notes were being played too, not just the same note in several octaves, as the diagram illustrates.

The upper staff of this Beethoven piano music indicates a right-hand melody which is doubled in octaves. The lower staff indicates the left hand is playing other notes that are not in octaves.

Bach understood that you don’t want to double just any note; doubling a note an octave higher or lower draws special attention to that note, so it had better be an important one, like the root note of the chord.

The music played by the mbira does just that – the root notes of the chords are doubled in octaves. Furthermore, on the mbira, many of the octave intervals are emphasized by putting notes an octave apart extremely close to each other. I call these notes “octave pairs”.

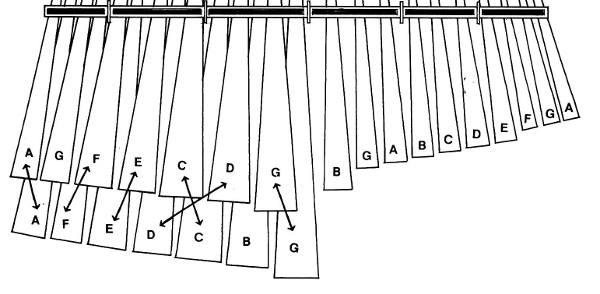

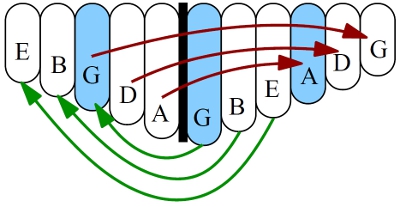

Octave pairs on the left side of the mbira are located for convenient playing.

The upper row tines on the left side of the mbira are generally an octave higher than adjacent (or nearly adjacent) tines on the lower row. There are important idiosyncratic exceptions, but it is clear that this instrument evolved this way to make these octave pairs easy to play. Generally, an upper-row note is played first, and the player slides their thumb off the upper tine to the left or to the right to strike a note, one octave lower, on the lower row. These octave pairs are an essential part of almost every mbira song.

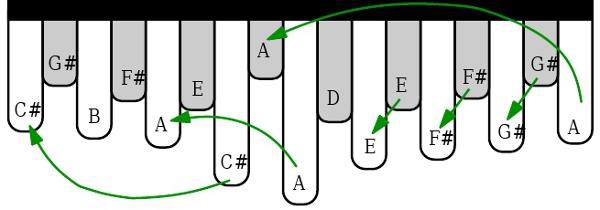

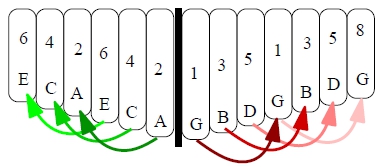

The upper-row tines on the right side of the karimba (also called the mbira nyunga nyunga) form octave pairs with their adjacent lower-row tines. On the (right side) of the 17-note Hugh Tracey karimba, you pull off the upper-row tine to the left to find its lower-row octave counterpart, as illustrated here.

Some of the octave pairs on the karimba. The pairs on the right are especially handy.

You can do the slide-off from upper to lower octave tines on the right side of the karimba, but there are two other common uses of these octave pairs:

1) On the karimba it is easy to simultaneously play two notes an octave apart. The technique is to play the upper note with the right index finger and the lower note with the thumb. If you can’t learn to use the index finger, you can also do the slide-off with your thumb, but you need to move so quickly that there is no discernable delay between the upper and lower notes.

2) The karimba also uses octave substitutions – after playing a melody one particular way, one or two notes an octave higher might be substituted for their original lower-octave counterparts.

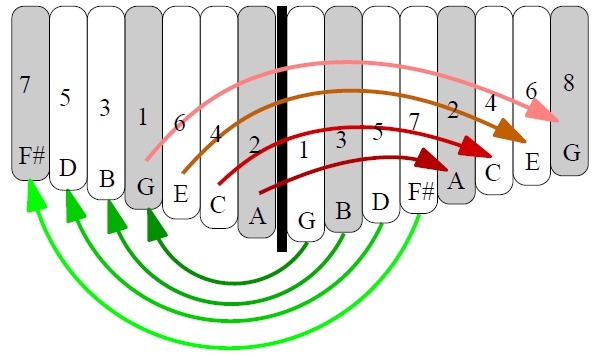

While the note layouts on both the karimba and mbira are idiosyncratic ones, most kalimbas have alternating left-right note layouts. On any such kalimba with a 7-note scale (the diatonic kalimbas such as the Alto and Treble, for instance) or a 5-note scale (that is, a pentatonic kalimba), octaves will be on opposite sides of the kalimba. Study the tuning chart for your kalimba and find all of the octave pairs, and become friends with each.

Octave pairs on the Alto kalimba are on opposite sides from one another.

If octave pairs are on opposite sides of the kalimba, this permits you to play a melody note high up on the kalimba with one thumb, and a supporting bass note an octave lower with the other thumb. The kalimba has real genius as a self-accompanying instrument, playing higher octave melodies and lower octave harmonies in sync.

Octave pairs on pentatonic kalimbas are also on opposite sides of the instrument.

Sometimes a scale will have six notes in each octave. Thomas Bothe actually has a tuning that is in part based on a four-note scale. A kalimba with an alternating left-right note layout that uses a scale with an even number of notes (four or six) will have octave pairs on the same side. This makes it easier to remember where the notes are, but more difficult to play melodies and chords together.

Kalimbas based on a six-note scale will have octave pairs that do not cross sides.

The most important lessons for you to remember: your kalimba probably has one or several octave pairs. If your kalimba is in tune, those octave pairs will all sound good. If your kalimba’s octave pairs don’t sound good, you should check the tuning and revise it if you need to.

Study the tuning chart for your kalimba, and find all the octave pairs. The notes in an octave pair will have the same note names, but one is higher, the other lower. Be aware of kalimbas like the Evil tuned Treble, or the African tuned karimba, as these instruments have redundant notes – two tines playing the exact same note, in the same octave.

You should become friends with each octave pair on your kalimba. Experiment with different uses of the octaves. Learn a short melodic phrase, and try playing it an octave higher or lower, as your instrument permits. And learn another short melodic phrase, and then substitute one or more notes an octave higher or lower to create an interesting variation. Learn to play each octave pair simultaneously to make a more powerful note.

Go forward with the faith that there is a deep logic to the location and orientation of the octave pairs on your kalimba. Use your mind and your intellect to uncover and understand those notes. Trust that over time, your body will come to internalize that logic, and your thumbs will know the way, even if you cannot say precisely what they are doing or why. That, my friend, is a powerful place from which to play.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades 8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba

8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and Magic

Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and MagicUse of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.