Use of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.

My friend Andrea Eckardt and I are back with another exotic Sansula tuning, showing the world just how easy it is for a Sansula and a guitar to make great music together.

The Sansula is made by Hokema in Germany. The tines of this exotic kalimba make a crystal-clear sound, amplified by the Sansula’s oval-frame drum body.

Today we are going take a very close look at how the guitar accompanies the Sansula; I dissect our improvisation “blow by blow,” and share six rules that can help any chording instrument (guitar, piano) successfully and gracefully accompany a Sansula.

At the beginning of the video (which should be playing automatically), we start playing a simple two-chord groove. I am going back and forth between C chords and Dm (D minor) chords on guitar. Andrea’s Sansula playing is flowing with my chord changes, and she changes the arpeggio she is playing to match my changing chords. At 0:19, I alter the chords slightly to CM7 (C Major 7) and Dm7. Andrea does not change anything, it’s not required. But this makes the music a little bit richer. It makes it feel like we’re starting to go somewhere.

From the beginning and up until 0:35, we have set the expectation on our music – something that repeats between C and Dm in a predictable way. But right at 0:35, Andrea stumbles slightly on her repeated riff – her timing was imperfect. And, rather than take this as a mistake, I take it as a signal that she is probably tired of doing the same thing four times in a row, and make myself alert for something new to happen. (I always tell my students to spend more energy listening to the other musicians than energy figuring out what to do next. And when you are that tuned-in, what they do will guide you in what to do next.)

So, when Andrea jumps up high into something new (at 0:37 in the video), I am right there, ready to go with her – I rise up to play the Em7 chord, which I haven’t played at all up to this point, and I then alternate with Dm7 for a while. And the result? A cool and smooth jazzy feeling in the combined music. Yeah! That is the magic of improvised music when you are tuned in to your partner.

At 0:42, as I change down from Em7 to Dm7, you can almost hear Andrea listening. She hesitates. The guitar is holding the rhythm and the harmony, and she can afford to hold back and take in the scenery of the changes. Then at 0:46, when the guitar returns to the Em7 chord, Andrea pretty much knows what I am going to be doing for a little bit – alternating between Em7 and Dm7. This gives her a bit of freedom, and she goes to town with strength in her Sansula playing.

At 0:54, I turn the chord progression around by “going to the V chord” (the [Roman numeral] five chord). In this song, the “V” chord is G. Note that this is the first time that I play G in the song. I play it twice, here and the second-to-last chord of the song. Each time I play the G is significant. That is the way western music – and also a lot of African music – works. When you hit the “V” chord, that is a signal to the other players, to the audience, to the dancers, to everyone, that we are turning around and going back to the home chord. Which chord is the home chord? Music usually (but not always) starts on the home chord, and I started on the C chord, remember? And also, the key of the Sansula may give you a hint: C Major! And of course, that “V” chord being G? C=1, D=2, E=3, F=4, and G=5. So, if G is the turnaround chord, that is a good clue that we are turning toward C.

And then I wind it down with a little bit more of the C / Dm thing. Near the very end at 1:10, I go back to the G chord (“V” chord) to announce a final going home to the C – actually here it’s the CM7 chord, which to me sounds like rainbows, butterflies and unicorns.

Andrea is a great and intuitive musician and she does a great job with her improvisations. Her Sansula playing is the shiny object that you are paying most attention to in this video, but in spite of all that, it is the movement of the guitar chords that is driving the music.

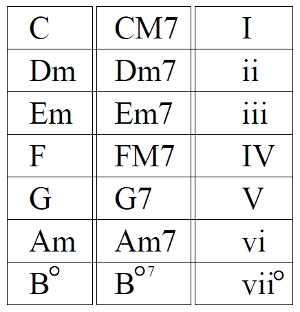

The chords listed to the right are the basic chords that are made up of notes in the key of C. I can play any of these chords and there is a good chance that they will work with the notes Andrea has on her Sansula. They might clash – I could play E, and Andrea could play F, which would not be great. But we seem to avoid that sort of pitfall.

How? Well, there is a certain amount of magic going on here, but underpinning that magic is the fact that my guitar playing follows some simple rules for improvisation. Primary among them: I do not venture outside the standard chords in the key of C.

The chords in the left column of the diagram are the triads – three-note chords made up of the 1, 3, and 5 of the chord. The chords in the middle column result from adding a 7th, and are slight flavor variants of the left-column chords. The Roman numerals in the right column are not tied to any key, but represent how far up the scale the chord is. People who know music theory live here mostly. And so do I, when I say “Go to the V chord.” The “o” superscript means B is a diminished chord. Don’t worry, usually I skip over the diminished chords.

A second rule: If you are playing chords without any organizing thought, that is the musical equivalent of finger painting with all the colors and making brown. Instead of making brown, try using just a few of these chords to create a simple structural element in the music. That is what I do in the first bit of music, alternating between C and Dm. What could be simpler than two chords? Well, one, but there is no motion in one chord. To keep from getting bored, I switched the C / Dm element to CM7 / Dm7 – but that is just a small variation, and I am clearly still working with the same color scheme.

A third rule: After I did the C / Dm section FOUR TIMES, and when I sensed Andrea was becoming impatient, I created a second section. That section, with Em and Dm, is related to the first section. The Em is a substitute for the C. If you know the notes that make up these chords, then you know that 2/3 of the notes in Em and C chords are the same, making the chords of the first section and the second section almost the same.

A fourth rule: Understand the suggestive power of the “V” chord. Now, if you use the “V” chord at random, or before the music has progressed to the point where a “V” makes sense, a “V” chord can be premature and give a false warning, too early. As I’ve discussed, I built a first section (repeated four times), then a second section (which I only repeated twice) – and THEN when I felt it was time to go back home, I threw out the V chord, and paused slightly, as if to say “Well done! Let’s go home now!”

A fifth rule: When I drive the music back home with the “V” chord, I really do go home, back to the first section I created at the start. The listeners and the players will remember it. It really does feel like coming back to a safe harbor… even though we didn’t travel very far away.

A sixth rule: Set up expectations by repeating something… and then break those expectations by going somewhere else. When you confirm a listener’s expectations, they feel they understand what is happening. But when you break expectations that you have previously established, it surprises the listener and keeps their interest level high.

When I play guitar to support a kalimba player, I am always aware of exactly what notes are on that kalimba. I am careful not to lay a trap for the kalimba player (ie, I don’t throw out a chord that will likely sound horrible with the Sansula’s notes). But even more important, I feel that I am creating a landscape, a topography of hills and valleys that pull and push on the kalimba player. I try my best to spin them up and push them out into the wilderness, and then I wind them down and pull them back home. And harmony is the main way that I create this landscape.

As an exercise for the guitar-playing or piano-playing reader: consider some other key besides C – lets say G, or D, or A, or E. Populate a table with named chords, just like the table we looked at for C chords. The Roman numerals will not change at all. The symbols will all remain exactly the same, only the chord names will be different. If you are in the key of E, that top chord will change from C to E. The second chord will change from D (a whole step above C) to F# (a whole step above E). In order to proceed, you need to know, or to figure out, what the notes are in your key (in terms of sharps and flats)… and then you can just plug those notes into the chords, going up the scale (or down the chart).

By the way, C major is one of the tunings I developed, and I have done a lot of work with it on Sansula. I created a great instructional download for C Major Sansula, which you might be interested in getting.

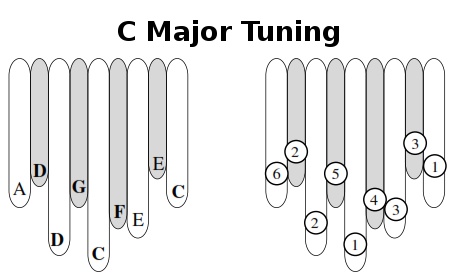

You can retune your standard Am Sansula into C Major yourself, or you could get a C Major Sansula from us directly. Note names with bold font (D, G, F, and C) in the diagram above require retuning from the standard A minor Sansula tuning. Non-bold note names are the same notes as the standard tuning. The numbers refer to the degree of the scale: C=1, D=2. Why are they not Roman numerals? Because they are individual notes, and the Roman numerals represent chords.

By the way, you might imagine that the key of C major might be the least exotic tuning – but the Sansula’s standard A minor tuning is pretty exotic itself. When I refer to an “exotic Sansula tuning,” I am using the world “exotic” to indicate any non-standard tuning. I suppose “exotic” is all relative. Anyway, it seems that anything you play on the Sansula is exotic.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades 8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba

8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and Magic

Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and MagicUse of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.