Use of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.

While Hugh Tracey is best known for the Hugh Tracey kalimba, I believe his most important work was the assemblage of 35,000 field recordings he made through the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s of traditional music across sub-Saharan Africa.

These recordings captured music across Africa just before much of the traditional music was eclipsed and even erased by modern European influences such as the western scale, choral church music, and western popular music, which were propagated by radio and recordings.

Today, Tracey’s historical recordings are alive and well and accessible. Anyone can listen to them. Their story follows, as well as how they are being brought to life in our time.

1954 was the year that Hugh Tracey’s legacy came together: he founded ILAM, the International Library of African Music, which would house the collection he had amassed on reel-to-reel tape of over 35,000 field recordings of traditional African music. He also filed the business license for AMI, or African Musical Instruments, the shop that still makes Hugh Tracey kalimbas today.

Tracey’s business plan was brilliantly symbiotic: the non-profit library ILAM would inspire interest in and lend credibility to the new Hugh Tracey kalimba; this would result in sales and profits for AMI. Those profits would turn around and help fund ILAM and its activities, promoting more scholarship about African music.

If you haven’t heard of ILAM, it is well worth a look. I invite you to:

search the historic recordings archive.

One day recently i was driving along in my car, listening to PRI’s radio program “The World”, when to my amazement, out of my car radio speakers pops the melodic kalimba refrain to “Ndamutemba Nyanga,” one of the songs in my new book “About 30 Traditional Karimba Songs.” I had delved into the digitized ILAM archive and there I had found this song and several others that work on the African tuned karimba, many of which are included in the book. (Several are also in my Student Karimba book, and I am looking forward to diving back into the ILAM archive to look for more musical gems.) I listened further and learned that the host of “The World,” Marco Werman, was interviewing Nabihah Iqbal, a London-based DJ who goes by the name “Throwing Shade.” Ms. Iqbal has created modern electronic music that is based upon and includes traditional recordings from the ILAM archive!

Speaking about Hugh Tracey’s legacy of thousands of original field recordings, Nabihah Iqbal told Mr. Werman, “If those recordings do end up sitting on a shelf I think we are not doing justice to the prolific work Hugh Tracey carried out in his lifetime. I’m pretty sure he didn’t make all those recordings so that none would ever hear them ever again.”

Listen to Nabihah’s music and the story on “The World”.

If you are looking for inspiration for your music, you may want to search through the ILAM database yourself. It’s a precious world of history and music and it’s available anytime, at your fingertips. You don’t have to go to Africa to be educated and inspired.

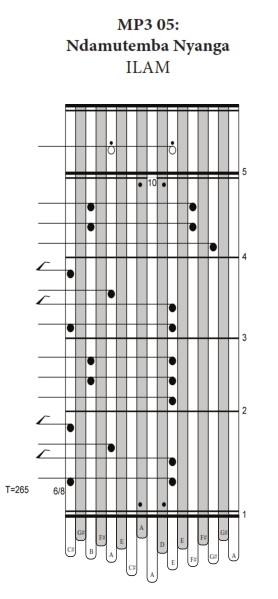

You can learn to play the traditional song Ndamutemba Nyanga

which DJ Nabihah Iqbal used in her modern composition.

Also included in Marco Werman’s story was Chris Pedley, who organized a recent concert to “repatriate” sound recordings Hugh Tracey had made in Malawi in 1950 and 1952. First, the original field recordings were played for the audience, followed by the modern songs based on the original field recordings. The Malawian people had no knowledge of the traditional music. That music had been lost to their national consciousness. This concert helped connect them with their own history, which would have been totally gone had Hugh Tracey not captured it when he did.

There is a widespread perception that the white Europeans just used and took from Africa. I think it is true that Hugh Tracey did take from Africa: he took about a dozen different specific design features of various African thumb pianos and re-engineered them into the Hugh Tracey kalimba – the main instrument that I sell. And he took these field recordings. But it is also true that Hugh Tracey gave back a great deal to Africa: he documented the old music at a time when it was being forgotten. In many places, that music now has been completely forgotten. But that music is not gone, it is just resting at the ILAM, and you and everyone else in the world can go and get it.

If you want to learn to play some of this traditional African music, I suggest you consider getting a Hugh Tracey African tuned karimba and the new “About 30 Traditional African Songs for the Hugh Tracey African Karimba” book or download.

The media widget below plays my own recording of Ndamutemba Nyanga, contained in the “30 Traditional Karimba” book or download. This music matches the tablature above.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades 8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba

8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and Magic

Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and MagicUse of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.