When I play kalimba by myself, I usually go pretty deep. It’s like meditation, only more playful. After playing for 20 or 30 minutes, I am usually in a very peaceful state. I seem to look within while I play, and when I stop playing, I find that I don’t quite focus on anything in this physical world. It usually takes me five or ten minutes to re-acclimatize to the world. WARNING: Do not operate heavy machinery while playing kalimba! (So far, there is not a call to raise the legal age for kalimba playing to 21.)

Playing kalimba with someone else can also be a very creative experience, and here I will discuss doing that very thing, using a kalimba song that is historically important to explain and illustrate.

I was playing kalimba together with a friend, and the song we were playing on our 17-Note African Karimbas was “Wa Kalulu”. She had originally learned it from my Student Karimba book, but had transferred it over to the 17-Note Karimba. By the way, “Wa Kalulu” may have been the very first traditional kalimba song to be written down in western musical notation, by A.M. Jones in 1950 – more on that at the end of this article.

It had been so long since I had played “Wa Kalulu” that I couldn’t remember how it went – but my friend did. So I relearned it from her, and with about 5 minutes of struggle and practice, I had the song down.

As you can see in the tablature below, it is just a tiny little song, but it has a great, “merry go round” happy feeling.

The illustration is a page from the “30 Traditional African Karimba Songs” download, available only at Kalimba Magic.

My friend was happy to hold down the song’s “basic part” by playing what A.M. Jones had written down over 66 years ago. This allowed me to drift off into finding different possible accompaniment parts.

What that looks like: my friend is solid, playing the same line over and over. It keeps coming back dependably. I want to create something that is true to this basic line, that is somewhat different, which amplifies the main line’s essential message. The part I create should add something more to the music without disrupting the original line.

I’ll do something a little different each time. Some of my attempts are garish, or have parts that stick out in the wrong way, or go against the harmony implied by the original like. First, seek rhythmic compatibility. Then seek harmonic compatibility. Last, seek melodic compatibility. When I fall into something that works, I hold there for 4, maybe 8 or more repeats, like a yoga pose, stretching into it. We have arrived. And then I shift back into the river of change, fishing for another great phrase to bring back and pose with.

Soon, my friend is going to be ready for me to hold down the steady line while she explores different variations.

My friend reflected out loud that even though this little snip of music is only 40 seconds long on the recording I did for the book, we seem to have played it for over ten minutes. Yes! Almost an infinite number of possibilities exist hidden within the starting idea for a song. If you do the math – and I have on occasion but will spare you – there are millions of possibilities for even the simplest phrase. You could literally spend the rest of your life seeking out all possible variations of a phrase and barely scratch the surface. I don’t intend to suggest such boring work – it could be a life sentence – but if there are so many millions of possibilities, how easy must it be to find five or ten of them? And five or ten variations is plenty to have a grand time with.

The ancient Africans gave us the form – a cycle of music, 24 or 48 short beats long, and a few hints for chord changes. They gave us the melodies and harmonies. And they gave us the shape of the song: to start with the melody and slowly change it and change it, progressing down the road toward inner understanding by turning that melody inside out with ever changing variations. And when you are tired of the slowly-changing scenery that the musical variations weave, come back quickly to the song’s starting point. On the way back to the starting point, try to touch some of the scenes you passed through, but don’t spend too much time as they are just to remind us of the journey we just took.

How wonderful it is to take this kaleidoscopic journey with a friend, or friends. Slowly tilting, then pulling me inward. Some of the musical variations are traditional ideas. Some are my own inventions, and some seem to come from another place altogether. All that matters is that when I’m in the groove, I twiddle my thumbs and, braiding into the core main part provided by friend, the music emerges from my head and my heart and my hands, and into the world.

The song “Wa Kalulu” was first published in western notation in 1950, though the tune itself might be as old as a millenium. A.M. Jones, a Christian missionary traveling in Africa, included “Wa Kalulu” in a scholarly journal article: “The Kalimba of the Lala Tribe, Northern Rhodesia”. Jones wrote about the making, the music, and the cultural uses of a 9 or 10 note instrument called the kankobela, which he refers to generically as a kalimba.

By the way, regarding the name “kalimba”, Jones’ article appeared several years before Dr. Hugh Tracey started making and selling his own version of the African instrument under the name “kalimba” – which helps show that “kalimba” was probably a generic name for the thumb piano long before the “Hugh Tracey kalimba” came on the scene.

Looking at the tuning of the kankobela in the article reveals that it is the same instrument as the Student Karimba, with an extra note added. Long before his article was published, A.M. Jones first visited the Lala tribe in the 1930s. At that time their kankobelas had 9 notes. When he revisited them in 1950, they had added a 10th note to their instruments. One would think that the music then would be different, but essentially all of the songs they played had been written before the extra note was added, and Jones saw that the players seldom used the extra note.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Christmas in July 2025

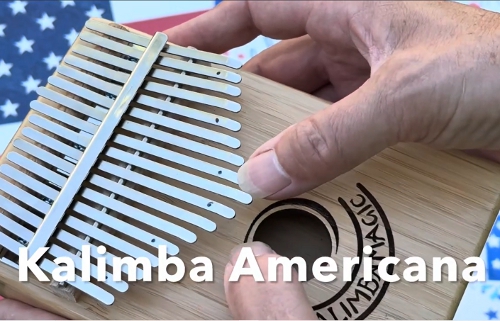

Christmas in July 2025 Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba

Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba