During my 2008 visit to his Grahamstown, South Africa home, Andrew Tracey (Hugh Tracey’s older son), long-practicing ethnomusicologist and musical performer, shared recollections of his father’s work, the early Hugh Tracey kalimbas, the layout of the Hugh Tracey kalimba, and his ethnomusicological research showing the karimba to have the prototypical tuning that was passed down to subsequent instruments such as the mbira dzavadzimu.

We are featuring this article once again as we celebrate Hugh Tracey, Andrew Tracey, and all Hugh Tracey kalimbas this month.

Here I am in July 2008 in Grahamstown, South Africa, interviewing Andrew Tracey, Hugh Tracey’s oldest son, former

director of the International Library of African Music, and owner of AMI.

If you are reading these words, you already have heard of Hugh Tracey, who may be best known for designing and popularizing the

Hugh Tracey Kalimba that went around the world

and started the kalimba craze of the 1960’s, which is still echoing today. But perhaps Tracey’s most important work was recording

traditional African music across sub-Saharan Africa. This

British ethnomusicologist travelled about Africa from the 1920’s through the 1950’s, made high quality field recordings of traditional African music,

and documented traditional instruments, note layouts, and tunings.

In 1954, Dr. Tracey founded the International Library of African Music

(ILAM) to house his collection of

materials and to make them available to the research community. Shortly

after that, he began making kalimbas of his own and founded African Musical

Instruments (AMI) to manufacture them.

Following in Hugh Tracey’s footsteps was his son Andrew, who

began his own field work in African ethnomusicology in the late 1950’s. This work was interrupted by the successful run (1962-1968) of the hit musical review

Wait a Minim which he co-wrote and performed with his brother Paul Tracey among many other talented artists. This satirical, political and social review ran in Africa and then London for two years each, then to Broadway for another year.

Upon their father’s death in 1977, Andrew

took up Hugh’s position as the director of ILAM, and remained in this position

until his retirement in 2005. A life-long lover of music, Andrew has impacted

the direction of AMI by introducing the African-tuned karimba to AMI’s

stellar lineup of musical instruments. Andrew succeeded in finding what his father had sought but not found: Andrew developed a unifying theory of the evolution of the note layouts of all traditional kalimbas in southern Africa. In effect, Andrew pulled back the veil formed by the many confounding changes people had made to the kalimba over the centuries, to lay bare what could be the original kalimba from about 1300 years ago.

KM: Where to start?

Andrew Tracey:

It all starts from my father’s early experience as a teenager in his brother’s farm

in south Rhodesia in 1921, and his early research experiences, which set him on the way.

KM:

Tell me about your father’s early experimentation with African music in the 1920’s.

Andrew Tracey:

I wouldn’t say it amounted really to experimentation—it was more excited

discovery. He had had no special training in anything very much. (After his father’s untimely death the family could no longer afford to send him to university as his brothers had been. His

mother didn’t know what to do to prepare him for Africa, and had sent

him to a boot-maker for a little time before leaving!)

He was very proud of the first instrument he made at his brother’s tobacco

farm at Gutu. It was a 5-string banjo (other members of his family had played

banjo in England), made in the manner of the local Karanga

gandira tambourines with a buckskin top. He could not get any wire

thick enough for the bottom string, so had to use a bootlace, and tuned

it one octave low! He even played this instrument on BBC radio in England

when he went home for a break after some years and sang some of the

Karanga songs he had learned. I wish I had a picture of it.

At one point he

attempted to learn to play the njari mbira which was played around there,

but didn’t get very far, and he invented a kind of notation for it, but years later we found that neither of us could decipher it. He spoke the language and sang

of course, and was competent on the Karanga drums. He heard all the music

in the region, always with Babu Chipika, his first and best African friend, who played the chipendani mouth bow and worked on the farm. (See accompanying photo of Hugh Tracey recording a mouth bow player). Babu helped to manage the research trips made by Hugh from 1929 to 1932 around eastern Zimbabwe with a Model A Ford pulling a Model T chassis as a trailer, and saved Hugh’s life when he contracted cerebral malaria. Babu also helped organize the two trips that Dad made with about a dozen Karanga musicians to record in Johannesburg, and then in Cape Town, when Dad had heard that there was an EMI recording team visiting. These were the first ever recordings made of African music from Zimbabwe (Southern Rhodesia).

The funding for this early research came from the Carnegie Corporation, channeled

through the Southern Rhodesian government’s education department, via an administrator called

Jowitt. When Dad’s report to Carnegie appeared on his desk, Jowitt saw that it came

down heavily on the destructive effect that the missionaries were having on the

traditional music of the country (particularly the evangelical Protestants), so he

held onto it and never passed it onto Carnegie. (It was government policy to

support the missions as the spearhead of African education in the country.)

It was only forty years later, not long before he died, that Dad discovered for sure that his work had been silenced. By this time of course his ground-breaking work had been overtaken

by others, even including me, so he lost that pioneer renown he could have had

much earlier. But he more than made up for it later on! That experience was one

reason why he left Zimbabwe in 1933 and went to work with the South African

Broadcasting Corporation. His views on missionaries also turned him completely

off them and religion for the rest of his life.

KM: When I read about your father, it seems that his dreams of capturing

traditional African music before it was destroyed by western musical influences –

and his recording trips – just kept getting bigger and bigger until his life just sort of

exploded with the big trips in 1952 and 1957, along with the founding of ILAM and AMI.

Speak to us about that arc of Hugh Tracey’s life.

Andrew Tracey:

His recording started in 1929 and then 1932, and there was another

burst with the Zulus when he was in charge of the SABC [South African Broadcasting Corporation] station in Durban,

which is a Zulu area. And then he began really recording more in 1947

when he moved to Johannesburg and got sponsorship from the Gallo

[Record] Company. Those [1952 and 1957] were big trips. But there

were others…1950, early 50’s were the biggest trips. But there

were very many other shorter trips around southern Africa. ILAM started in

1954, but he was doing ILAM sort of work for many years before that.

KM: The big trips your father undertook with significant funding

in 1952 and in 1957—were you able to accompany your father into the field

on these trips?

Andrew Tracey:

No, I was still at school. I only joined him at the end of 1959,

and I actually missed all his big trips, much to my regret. Any

of the recording I did with him was at ILAM or at one of the mines. I

went to Chopiland in Mozambique with him once.

KM: Like your father, you have a doctorate in ethnomusicology?

Andrew Tracey:

We both received an honorary doctorate in ethnomusicology, his from Cape Town

University, mine from the University of Natal (Durban).

KM: Are these honorary doctorates given for some specific work, or

are they for an overall recognition of a lifetime of ground-breaking work in the

field?

Andrew Tracey:

They are for an overall recognition.

KM:

The first time I ever came across your name was while reading

one of the booklets that used to come with Hugh Tracey kalimbas back in the

1960’s. (By the time I bought my first kalimba in 1986, the kalimbas didn’t come with

these booklets anymore.) In a photo from the musical review Wait a Minim,

you and Jeremy Taylor were playing guitar, while brother Paul Tracey played

kalimba. Did you write that booklet?

Andrew Tracey:

Yes, along with my father. I think most of the phraseology was mine (and my

brother’s). I wrote it from the point of view of a trained musician;

my father was not a trained musician.

KM:

One bit of phraseology from that booklet struck me as odd: "A New Musical Instrument from

Africa". I had been told that the kalimba was actually an ancient instrument, yet the book

called it new. And then I figured it out: the Hugh Tracey kalimba is sort of a hybrid

instrument—between the traditional African and the Western musical traditions. In your mind, how do you ground the Hugh Tracey kalimba in African music and traditions?

Andrew Tracey:

What you say is perfectly right—it is between the two traditions, and has some of the

good points of both. What I see as some African strengths it shares with many other

African instruments are: its person-friendliness, intimacy and portability— a lot of music

in a small size— its responsiveness in that it often gives you back more than you realize

you are putting in—because it can encourage you to think of physical patterns as

inspiration just as much as melody, the normal western approach. What one plays

on the standard western-tuned kalimbas does not necessarily turn out very African,

because the tuning and the layout of the notes were designed to make it available to

western musicians. But the freedom which the African layout gives you allows you to

approach it with more of the creative spontaneity of the African musician, which can

only be good, particularly for all those unfortunate westerners who are stuck in the

typical paradigm of traditional classical music education. One can play it in both

mind-sets, African and western. Perhaps this last sentence says it best.

The kalimba is African with a tuning that enables you to play western diatonic

melody and harmony easily. Totally African. Dad realized that if you try to

produce an instrument with any of the African tunings on it, which are

largely irregular—the scale doesn’t go in a straight line or anything easy—that it would be hard for it to catch on with the public.

The idea of the left-right scale is also an African idea originally. It is

much used on the likembe, played mostly around central Africa. It started at

the mouth of the Congo river, and was spread, according to Kubik’s research,

by porters for the Belgians, so it spread all over the Congo and spread into

Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, a lot in Angola, all from its source in the

Belgian Congo. That instrument had some irregularities, and

Dad made a thorough left-right tuning, and he soon realized

this allowed western harmony – you play two notes next to each other, and

you get the basis of western harmony, which is the third.

The kalimba itself doesn’t come out of any African tradition, but

you can play African music on it, especially guitar styles—they

go on it pretty easily.

KM: But aren’t the African guitar styles derived from the mbira?

Andrew Tracey:

To some extent. Music that uses the three common chords [i.e., I IV V] is

the basis of almost all modern urban African music, and traditional

instruments don’t use that harmonic approach.

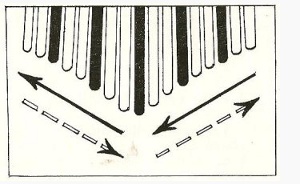

KM: There is a diagram in the original booklet which I saw long after I was an

accomplished kalimba player, but it would have been very helpful to me had I seen it earlier.

This diagram basically says: if you play low on one side, play high on the other side…and as you move up one side, move down the other side.

Andrew Tracey:

Yes, play low on one side and play high on the other side – that’s the

basic rule for finding a harmony. Of course, when you get to know the instrument more,

you choose the exact note you want.

KM: What was it like, discovering this entirely new instrument,

the Hugh Tracey kalimba—learning how to play it, discovering what it could

do—you and Paul must have figured out new things on it each day.

Andrew Tracey:

We first discovered the kalimba in the 50’s when we were in school. I remember the

first model was an all aluminum body. Curved body and flat top. I used to

hitchhike with it. I remember discovering how to do one-note harmony, then

three-note harmony and four-note harmony. How to play fast on it,

how to jump around, how to find your way on it. I remember learning all that

on the original instrument, which had a quite different sound.

KM: What do you think of the new Kalimba Magic instructional books?

Andrew Tracey:

They are painstakingly and beautifully done—I’m glad you moved from the

bottom up [in your tablature], because that seems natural to me. But I think it would be

much quicker not to work through that, but to learn from somebody.

I’ve never used written music for kalimba, but your books seem very thorough

to me, if the person learning needs that sort of approach. But with all

mbiras, the best way to learn is being shown by someone.

KM: After touring with Wait a Minim you had a good 10 years

before your father died, when you took over at ILAM and your wife Heather took over at AMI. I am guessing in some ways those years must have been the heyday of AMI.

Well, clearly AMI’s catalog is much larger now, and I think the quality of the kalimbas has

improved over the years—but between 1967 and 1977, AMI must have been on top of the

world. What was that time like?

Andrew Tracey:

That was the worst time for ILAM, because that was the time

that sanctions and world opinion [against South Africa’s apartheid

policy] began to bite. We couldn’t continue getting funding from

England and the States, and I moved ILAM down here [to Grahamstown,

where Rhodes University provided support] to keep it going.

Dad, of course, in the last years of his life, wasn’t really controlling

the company [AMI] very much, and he left a lot of the work to Heather [Andrew’s wife] and to the workers on the farm. The quality of the

kalimbas improved over the years because it had been standardized.

It took a long time for all the dimensions to settle down.

KM: How much of your job at ILAM was organizing your father’s work,

and how much of it was going out and doing your own work? How much of your

work was dictated by your father’s unfinished business?

Andrew Tracey:

I didn’t organize my father’s work. I was focusing on my own

research—my father encouraged that.

KM: Tell me about your research then.

Andrew Tracey:

My own research was basically on the mbira family in Zimbabwe and

neighboring countries. I wanted to establish the boundaries of that

music area, which are quite definable. It’s a huge musical area that

uses a common music system, largely based on harmony. That music

area includes several types of mbira, several types of xylophone,

mouth bows, pan pipes, flutes, and song, all using a certain system

of harmony.

KM: After retiring from ILAM in 2005, you came to work at AMI—what are you up to there?

Andrew Tracey:

My new office is here, but I don’t work here. I am more in the position of, firstly, owner

of the firm (I bought Paul’s share some years ago) and, secondly, general advisor e.g.

on musical and acoustical matters. My son Geoffrey is very musical but does not

have a great interest in the firm, so I am now in the middle of transferring 75% ownership

of the firm to

Chris Carver, who has done a tremendous job of bringing the firm into the

black, mainly through his development of the marimba sets. However I am still strongly

involved at ILAM, for instance in sorting, identifying and cataloging all my father’s

collections, including recordings, photographs, instruments, books . . .

KM: What a lot of work! If a kalimba enthusiast were to travel

to Grahamstown, South Africa,

and wanted to see ILAM, what would he or she see?

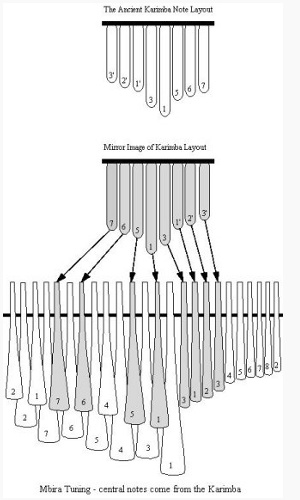

This diagram clearly shows the evolution from the ancient karimba note layout (the “karimba core”)

to the mbira note layout. Andrew Tracey asserts that every advanced

mbira or karimba has the same basic 8 notes of the ancient karimba, and in

the right order (though they have been flipped from right to left).

Note that the karimba has no 4th note,

but more advanced instruments such as the mbira DO have a 4th, but the

4th on the other instruments

(between the 5 and the 6 on the left side gray tines) is

stuck in, out of order.

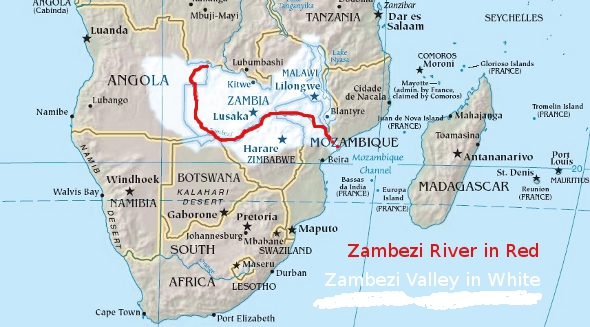

Andrew Tracey:

I see you put a small “k” there [in kalimba]. The kalimba is an instrument played in Zambia and Malawi, and if you spell it with an “r” [karimba], it’s an instrument played in the Zambezi Valley, in Mozambique and Zimbabwe. So it depends on what the enthusiast wants to see. We have a lot of recordings of the original kalimbas and karimbas of the Zambezi Valley. [Kalimba Magic now refers to non-traditional instruments as “kalimbas” and uses the word “karimba” to refer to that family of traditional instruments that Andrew mentions here. This seems to reflect a consensus of usage among other knowledgeable kalimba enthusiasts.]

The Zambezi Valley in southeastern Africa was the hotbed of metal-tined mbira innovation. This is the region where the “kalimba core” originated, and it is also where the great karimbas and mbiras later developed from the “kalimba core.”

Andrew Tracey: And then according to my research, which I published in one of my articles in African Music, the 8-note karimba is probably the original mbira – the very first instrument of its kind in southern Africa, the grandmother of the larger kalimbas and mbiras. You can call it karimba, or mbira – it doesn’t matter what you call it. I called it the “Kalimba Core” in a paper I wrote in 1973. Those are 8 out of the 9 notes on the bottom row of the karimba which AMI makes. The note on the far right [the 9th note] is a duplicate we added. If you look at the karimbas in ILAM, some of them have a lot of duplicate notes, but they always maintain those 8 notes in the middle – they

all have the Kalimba Core. You can track those 8 notes through every type of mbira. But this note – the 4th note – [see diagram above – the inserted “4” on the mbira dzavadzimu is white and surrounded by gray notes which in this diagram indicate the notes of the Kalimba Core] is always in a different place on each different kind of instrument. When they added the 4th to the lower rank of the mbira, they put it in the right order, but it’s out of order on the upper rank.

This is how the mbira came about: sometime during the last thousand years, an instrument closely related to the Kalimba Core that had a hexatonic scale [the 6 note scale of the karimba, or 1-2-3-5-6-7] was encountered by a group of people whose music was heptatonic [music based on a 7-note scale, or 1-2-3-4-5-6-7]. On the various instruments they developed from the original Kalimba Core, or 8-note karimba, they found different places to put the extra note, and gave those instruments different names. Other methods they used to extend the instrument and its capabilities included adding rows higher or lower, and adding notes to extend the scales on the outside of the Kalimba Core. People are very inventive in that part of the world.

KM: OK, this is very technical here, but I think it illustrates pretty

well why Hugh Tracey did get that honorary doctorate and why he is known

as Dr. Hugh Tracey. In one of the series of

Tips of the Day on the Kalimba Magic website,

I was looking at an example of a traditional African scale which your father

documented in Hz (Hertz, a unit of frequency), and I was showing how to convert that scale in Hz

to the closest Western notes with some “cents” flat or sharp [there are

100 cents in a half-step] — and I realized these things:

So, my question to you is: what was the range of your father’s 4 Hz grid

tuning forks? I am assuming they covered an octave, but if it was between

400 Hz and 800 Hz, it isn’t really a problem for the scales. If it was

between 200 Hz and 400 Hz, the lower end of the octave may have insufficient accuracy.

Andrew Tracey:

About the tuning forks, my father and I have both been very aware

that the accuracy near the bottom of the set [of tuning forks] was half that near

the top, and made allowances accordingly, as far as possible.

We have often estimated notes to fall between the fixed pitches

of the forks, especially near the bottom end.

At one point I considered having a new one-octave set made with

all intervals an equal number of cents, but quickly gave it up when

I learned the price from the few remaining Sheffield companies

that still make forks. Forks are no longer used in industry as they were. [Electronic tuners had already become very commonly used.]

Another problem we had to overcome was measuring notes that

did not fall inside the one octave range of the set, when we had to

judge by estimating octaves.

All in all, the two sets of forks we have, I reckon,

have done an incredibly good job, for these reasons:

KM: African Musical Instruments (AMI) makes the African-tuned

karimba, which is a high quality workshop version of a traditional instrument

that you and your father studied years ago. Can you tell us a bit about

the tuning issues which relate to this particular instrument?

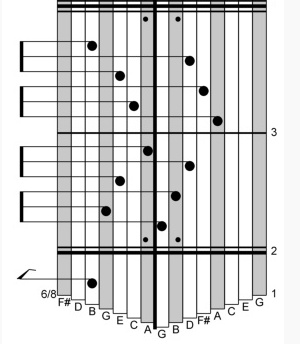

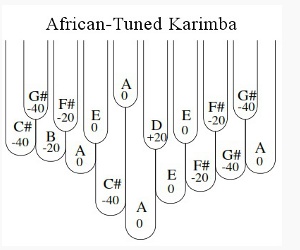

This is the tuning for the AMI African-tuned karimba: The numbers in the diagram represent cents flat or sharp (a half step contains 100 cents). While the AMI karimba comes with A as the root note, Andrew Tracey notes

This is the tuning for the AMI African-tuned karimba: The numbers in the diagram represent cents flat or sharp (a half step contains 100 cents). While the AMI karimba comes with A as the root note, Andrew Tracey notes

that traditional karimba keys are widely variable, depending upon

the size of the instrument. A larger piece of wood will resonate at lower

pitches and can accommodate a lower key, but all the intervals remain constant.

Essentially this shows that African musicians have relative pitch but not perfect pitch,

as is the usual case in the west as well. Andrew also remarks that the highest note

(the shortest tine) was first placed on a karimba by his teacher, Jege Tapera.

Andrew Tracey:

To talk about the particular tuning which we use for the African-tuned karimba…like most things, it is a compromise.

It is not exactly the same as any tuning I ever measured in the Zambezi region,

which all have their own unique sound. I had to choose something that would

convey a general feeling of Shona/Sena tuning, for instance: 1) by avoiding

anything as small as a semitone, which in our experience is very rare in

central and southern Africa, 2) by moving towards the feel of an equi-spaced

heptatonic scale, with a preference for its typical interval of between 20 and

40 cents less than 200 (and actually reaches a very high degree of precision

among the Chopi), and 3) in particular by flattening the third and seventh

notes of the scale, which are the ones most obviously and consistently

different from the Western major scale. It is a tuning that is accepted

by the [local African] musicians – you put it in their hands and they say, "Yes, that’s it!"

Of course, the [historic] karimbas you’ll see at ILAM all have other notes added; different people added different notes on either side of the original eight

notes. As long as you have those original eight notes, you can play

all karimba music in basic version. Those are the eight notes you see

as the basis of all mbira music in the Zambezi Valley.

KM: The flat third and the flat seventh are used in blues music—but these notes here are in between the natural and flat third and seventh.

Of course, guitars and harmonicas and the human voice can bend the note

to be between the western notes. And the karimba can tune to that precisely.

Andrew Tracey: Yes, those two notes have to be noticeably flatter

than western notes. But you shouldn’t think of the African tunings as

"bent western notes." Musicians who are raised with a certain tuning

don’t bend anything—it’s the right note! I don’t think, "Oh, these two notes

together make a 5th, it is just what it sounds to be.

KM: Actually, all of the 5th intervals on the karimba are perfect

5ths except for one.

Andrew Tracey: Is that so? Ah, you’ve got me there!

KM: The work done by you and your father started back when western

musical influences on rural Africans was fairly minimal. Maybe these

musicians had been exposed to choral singing by missionaries, but

the traditional tunings were still strong. What about now?

Andrew Tracey:

In fact, talking about mbira tuning in the modern day is almost losing its

point, because there can be very few players now whose ears are not

constantly being bent by recorded music on radio and TV. I doubt if

there are many musicians in most urban centers in Africa who are able

to hang onto traditional tunings. One can hear it easily for instance in

Harare. I think one would have to exclude the griots [travelling poets, musicians and storytellers] of Mali, Guinea, etc. in

West Africa to some extent, because they seem to have a sophisticated

and, importantly, a conscious knowledge of the several different tuning

systems which they use at various times on the same instrument (kora).

Musicians at this end [the southern end] of Africa are not nearly as aware of the fact that

tunings can differ from each other.

KM: On the other hand, in The Soul of Mbira,

Paul Berliner mentions mbira players in (now) Zimbabwe who take an old

traditional song and play it with exactly the same thumb and finger strokes, but

with a new and modern tuning to create a new song. This indicates awareness

of the different tunings, but also an openness to the transitory nature of

tunings.

Andrew Tracey: Yes, this is happening a lot now. I think

there were only a few tunings when he wrote that book, but now there are many.

They even give them names. I haven’t researched in this, but there

are so many Americans playing mbira. Someone might pickup someone

else’s tuned mbira and say, "Oh, this sounds nice." Maybe they want

a note to be more flat or sharp or something. But as to measuring,

it’s only really my dad and I who have measured the [microtonal] tunings.

KM: Andrew, are there any other traditionally tuned instruments such as the

karimba that we might see coming out of AMI in the future?

Andrew Tracey: I would love there to be!

Traditionally tuned—not just traditional. Well, we make the amadinda

and the akadinda.

A good place to find out more about Andrew is

the ILAM website.

By the way, when you purchase a Hugh Tracey African-tuned karimba, they

all come with an insert from AMI with six different traditional karimba tunes

from Zambia, Mozambique, Zaire, and Zimbabwe.

Andrew Tracey notated these tunes in his own form of tablature.

I have transcribed those six karimba tunes into KTabS format, so

if you have KTabS,

these songs will "play themselves" on your computer.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Christmas in July 2025

Christmas in July 2025 Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba

Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba