Use of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.

Percussionist, composer, author and educator B. Michael Williams specializes in mbira, frame drums, djembe, and contemporary percussion. His mbira books are a great resource for any student of kalimba. Here are a few selections from Mr. Williams that give us a glimpse at a compelling and unique taste of his thoughts and experience with karimba and mbira.

My mbira journey began with Andy Cox’s karimba and Paul Berliner’s book, The Soul of Mbira. Andy had made me a karimba. When he finished, we decided to meet at a music festival in Charlotte, where we met up with Richard Selman. Richard played in Chartwell Dutiro’s internationally-diverse mbira group, “Spirit Talk Mbira” and was also a budding mbira maker. The band on stage was loud, but Andy wanted me to try out the new instrument. I was eager to oblige him! We found a somewhat quieter spot behind a vendor’s tent. It didn’t take long for the cops to show up wanting to know what we were up to. We had to convince the officers that we were not engaging in any nefarious activity, so Andy showed the gentlemen the karimba and began to play it for them. At first, they thought it was some kind of bizarre weapon (one of them quickly moved his hand to his revolver). We were warned not to “hide” behind a tent at a music festival ever again (a promise we have kept to this day, after 25 years).

The first tune I learned on that karimba was “Butsu Mutandari” from Appendix III in the back of Berliner’s book. It took a while to figure out how to translate the vertical lines and numbers into something that sounded like a song, but with a lot of practice, I began to get the hang of it. I found a recording by Dumisani (“Dumi”) Maraire that included “Butsu Mutandari. ” Listening to the recording while following the notation made for a much more pleasant learning experience! Another song on the recording was “Chemutengure.” During the learning process, it occurred to me that I was able to “see” the karimba keys in my mind as I deciphered the vertical rows of numbers. Listening to Dumi playing and singing was an inspiration! I listened carefully to the lyrics and wrote down each syllable. This was meticulous work, but I figured if American opera singers can learn Italian arias phonetically, I could do the same with Shona! After many repetitions, everything fell into place.

Once I learned to sing and play at the same time (which I figured out by writing the vocal syllables under the corresponding keys in the tablature notation), I was determined to learn the meanings of the lyrics. Sometimes I could rely on liner notes, but more often I contacted my Shona-speaking friends for help. I sent them an email with my phonetic spellings, and they replied not only with the words’ meaning, but also with corrected spellings! I resolved to never sing a Shona song in public unless I knew the song’s meaning.

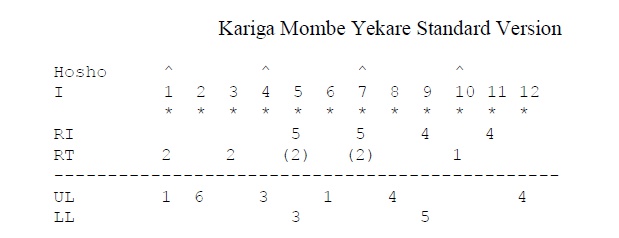

With a few karimba tunes in my pocket, I moved to the larger more complex mbira dzavadzimu. It seemed to me that I could come up with a horizontal tablature that would be easier for players to follow. This tablature notation is my “storage and retrieval system.” As the student progresses with any tablature system, continued practice creates a muscle memory that becomes second nature. The numbers fade away and the body now remembers. If we forget a song along the way (which can happen if we don’t maintain our repertoire – trust me) we can always go back and retrieve the notation.

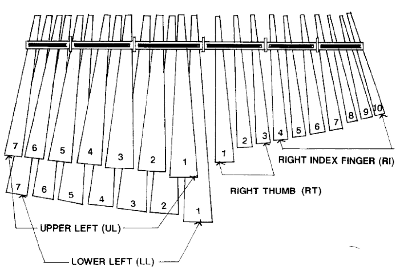

Tablature for one of the four phrases for the mbira song “Kariga Mombe Yekare,” from Williams first mbira book. In Williams’ tablature, RI stands for “right index finger”, RT for “right thumb”, UL is an upper row tine on the left, and LL is a lower row tine on the left.

This is a tricky subject, and one that should probably be avoided in general (sometimes it’s not in our best interest to “go there.”) In my studies of African music (frame drums from North Africa, djembe from West Africa, and mbira from Zimbabwe), I have come across some western “purists” who say we have no right to play the music of another culture, much less write it down, and I have received a good bit of criticism for my tablature notation. I once heard someone discussing those who play western music (generally folk songs, but also the occasional pop tune or original composition) on mbira or karimba. There are some who disparage the practice as appropriation (or perhaps mis-appropriation). Appropriation (as far as I am concerned) was largely responsible for the spread of jazz through a continuum including “field hollers,” folk music, blues, r&b, early rock & roll and other popular western styles. In Africa today, bands such as Oliver (Tuku) Mtukudzi and Thomas Mapfumo and the Blacks Unlimited employ electric guitars, keyboards, and drum sets to play both traditional Shona music and covers of American and British rock & roll (which they call “copyright music”). I view this phenomenon as a joyful exchange of information between cultures. Never have I met an African who was critical of my playing and transcribing their indigenous music. Indeed, they have been enthusiastically supportive and honored by my interest in their culture. I consider myself honored to have the opportunity to play this unfathomably deep and beautiful music.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades 8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba

8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and Magic

Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and MagicUse of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.