A main part of the philosophy of western musical instruments is to provide as many sonic possibilities as possible – hence the piano keyboard, with seven octaves of fully chromatic notes.

A main part of the philosophy of the kalimba is that it has exactly the notes it needs to create a particular scale or a particular song. Every note on a kalimba is important and useful. A particular kalimba’s scale, or tuning, will span a particular “music space” which contains the musical possibilities of that scale. And there are “way many” music spaces and there are also “way many” kalimba tunings.

One of my most favorite activities is to explore new kalimba tunings and their music spaces – ie, the different possibilities these tunings create.

However, as much as I love to explore and map all of these exotic music spaces, sometimes I forget to cover the most basic tuning of an instrument. In this post, I go back and analyze the Sansula’s standard mystical and enchanting tuning, and then I relate the Sansula’s tuning to exactly how I accompany the Sansula on my guitar.

This Sansula video is different from the earlier “Exotic Sansula Tunings” videos in one major way: in the earlier videos, I would lay out the chord progression on my guitar, and Andrea would sail over the top. In this video, Andrea controls many of the chords, and I on guitar must be responsive to her. You can see that right away in the video – she is controlling the changes, and I am going along. Or at least I am guessing where she will go, and sometimes she plays hide and seek.

There is no right or wrong way to do chords. When two or more people are playing together, they usually negotiate what the chords are going to be. That might be something as simple as “OK, I am just going to stay on this one chord.” It might be something like “OK, the guitar player will determine the chords, and the kalimba player has to follow.” It could be “The kalimba player is the boss, and the guitar has to follow what the kalimba is doing.” In this video, control actually is complex. In parts, the guitar follows the Sansula, but in other parts, the guitar introduces chords that Andrea is not asking for (such as the G chord, to be discussed below)… but they work nonetheless.

The worst-case scenario is that the players are not paying attention to the chords. For example, what if I played one chord on guitar, and the Sansula player played the notes from a different, unrelated chord? Those chords would likely clash. When this happens, the music suddenly sounds like it’s not ready for prime time. If the players are listening to themselves, they may make a bad face.

Yes, it happens, especially when playing improvisational music. But notice when the music sounds bad, and first ask yourself: is there a chord progression, explicit or implicit? Who is controlling or determining the chord progression? Is it more of a collaborative effort where different people are able to throw a chord out? Are the other musicians paying attention to the chord changes or not?

If there is a lot of confusion, you and your fellow musicians may need some education about how chords work. This is not a general treatise on how chords work, but it is specific to how chords work with the standard Sansula tuning.

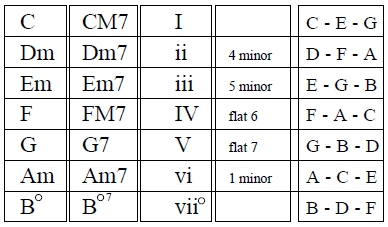

The chords listed to the right are the basic chords that are made up of notes in the key of C. This is almost the same diagram that we saw in the “C Major Sansula” article last month. The first column shows the name of the basic chord (the name of the 1-3-5 triad), the second column shows the name of the chord when a 7th is added, and the third column shows the role of the chord in music theory Roman notation.

The standard Sansula tuning is in A minor. The notes and chords in C major and A minor are the same. C major and A minor are relatives. A is the relative minor of C. The same chords will work for playing with a sansula in C major, or in A minor.

The last two columns are new. The second to the last column recasts these chords into the key of A minor, showing their function with the standard Sansula tuning. So, instead of Am being the “vi” chord (or minor 6), I call it the “1 minor”… because A is the root note. Normal notation would be “i” (the one minor), but for some reason I thought that might be confusing. The big takeaway here is that the third column shows the Roman numeral chords referenced to C major, and the fourth column shows Arabic numeral chords referenced to A minor.

And the last column spells out the notes in each triad – the C chord is made up of C – E – G as the 1 – 3 – 5.

I leave out the B diminished and the C major chords in the fourth column simply because I don’t use those chords in this post’s video.

The basic chord progression of the Sansula in standard tuning is between Am and F. In my guitar part while playing with Andrea in the video, I stick within that basic progression for almost the entire piece, but I also throw in the G chord in between the F and Am.

The Sansula in standard tuning does not have a G note. This is important – while you can’t play just any chord on the guitar, there are certain chords that will work even if the kalimba doesn’t have the root of the chord. The table above indicates that the G chord should, theoretically work with the Sansula. G# or Gb won’t work.

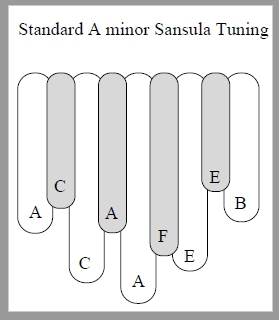

But really, why does G work? Let’s look at the notes in the standard Sansula tuning. They include only the notes A B C E F. There are three A notes, two C and two E notes. As there are five unique notes in the standard Sansula tuning, this makes it a pentatonic scale.

But really, why does G work? Let’s look at the notes in the standard Sansula tuning. They include only the notes A B C E F. There are three A notes, two C and two E notes. As there are five unique notes in the standard Sansula tuning, this makes it a pentatonic scale.

As a HIGHLY TECHNICAL aside (YOU CAN SKIP IT IF YOU LIKE), there is only one F and only one B – the F is a half step above E, and the B is a half step below C, which make dissonances if they are played together. (Try it – play the F and the low E together, then play the B and the high C together – that is dissonance.) BTW, most pentatonic scales remove the notes that make half step intervals, thereby removing possibility of dissonance. Furthermore, the interval from F to B is called the tritone, which is also fundamentally dissonant. (Try it – play the F and the B together.) The Sansula gives you the opportunity for those dissonances, but it limits the dose of the dissonance by only giving you one F and one B.

OK – back to the program of why the accompanying G chord works. Could it be that the other notes in the G chord are on the Sansula? The G chord has a root of G, a major third of B, and a fifth of D (see the last column in the table above). There is no D, but there is a B on the Sansula. This means that G minor, with a Bb for the minor third, would not work, because the guitar’s G minor’s Bb will clash with the Sansula’s B.

Back to the G chord and its notes G – B – D. As we know, there is no G and no D on the Sansula. But there are also no Gb, no G#, no Db, and no D#. This means that none of the notes in the G chord will clash with notes on the Sansula… except for C, which is a half step above B. But this is a “sanctioned dissonance” in western music – if you replace the G chord’s major third – B – with C, you have a 4th suspension, which resolves when you take away the 4th (C) and go back to the 3rd (B). Our ears are accustomed to hearing this dissonance and its resolution, so no problem there.

Another reason why G works with this song is because I use it only in passing. The chord progression I play most of the time goes:

||: Am | G | F | G :||

(The :|| is a repeat sign – it means as soon as you finish the second G, you go back to the beginning of the line and play the Am and go again.) If you don’t recognize it, this is the progression of “All Along the Watchtower.”

The A minor chord is made of A – C – E, and the F chord is made of F – A – C – in other words, all the notes in the triads of these two chords are on the Sansula. The Sansula can play Am and F all by itself, so of course, those chords will also work on a guitar played with a Sansula. However, the Sansula, as we know, cannot play the G chord.

But that’s OK. As we already know, the notes of the G chord do not clash with notes on the Sansula, so it isn’t bad. The Sansula has gaps where the G chord’s G and D should be, so it is like the Sansula is non-committal on the G chord. But the thing that really makes the G chord work is the fact that my guitar is never really landing on it. Rather, G is a place I pass through on the way between Am and F, or on the way from F back to Am. We are just passing through G, and even though there is not a strong resonance between the G chord and the Sansula, it is all OK because the main chords we are landing on – Am and F – do have a strong resonance with the Sansula.

It’s like this: In music, you can sort of do anything crazy or dissonant, as long as you don’t do it for very long, and as long as you start and end in a good solid place. This means you need to know those strong and stable cords on which is it good to start or end. On the Sansula in standard tuning, that would be Am and F.

Once you master the stable places and the dissonant places, you can begin to dance between them. Music that is all stable is boring. Music that is all dissonant is disturbing. Great music has stable places and dissonant places, and the dissonance is used with skill to bring us back to stability.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Christmas in July 2025

Christmas in July 2025 Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba

Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba