The “student karimba” is my own invention – or rather, it is my re-invention. I came up with the name, but Andrew Tracey calls it the “kalimba core” as well as the “original mbira”. I like to call it “the kalimba that time left behind.” While this little instrument is far from popular these days, it was mentioned in the first scholarly article on the kalimba written in 1950 by missionary A.M. Jones. I feel this simple instrument’s pattern is truly important because of where it stands in the history of all thumb pianos: it is the likely foremother of every southern African lamellaphone according to Andrew Tracey’s work. He asserts that it began to be used over a thousand years ago. Playing this “kalimba core” or “original mbira,” we are standing where ancient humans stood.

The kalimba core was very likely added-to over centuries to create other instruments. This post looks at ways that this may have happened and how the instruments maintain their original core, and how they and the music they play are related.

And the cool part? Most African songs that are played on the 17-Note karimba (for which Kalimba Magic has a lot of music) have substantial sections that can be played on these core eight or nine notes. What’s more, music that is intended for the student karimba can be played on the 17-Note karimba too!

It is believed that the kalimba core was probably an 8-note instrument. A ninth note was added sometime in the contemporary era, and the instrument I prefer, for many reasons, is the 9-note one.

The evolution of kalimbas from simple to complex by adding notes is not just an idea… in A.M. Jones’ 1950 article, the missionary tells that when he had visited the Lala tribe 20 years previously, in 1930, they had 8-note instruments of similar tuning to ours. When he returned in 1950, everyone had 10-note instruments, which they called kankobella . However, the Lala were playing the same old songs from 1930 and earlier that just required those basic eight notes, meaning the two newer notes were seldom used. (The music played on these instruments was likely many centuries old.)

A.M. Jones’ article illustrates how the creation of new, bigger kalimbas happens – the same old notes are retained so the same old songs can still be played, and more notes are added. There are basically three different ways this was done.

One method of increasing the tine number is to follow the existing pattern and add to it. If you look at the tine arrangement on the 9-note student karimba, you see what looks like wings – the three tines on the left side of the karimba and the four tines on the right. Also, one can see that those tine tips form a straight (diagonal) line. This is because these adjacent tines are tuned to adjacent notes in the scale. More notes could be added by continuing up the scale. In fact, this is how the 9-note student karimba was made from A.M. Jones’ 1930s 8-note instrument, by adding the far right tine, which is the next logical step. It is also tuned to the same note (and pitch) as the 3rd tine from the left. Having two tines with the same pitch permits us to play a trill.

By the way, this tablature is for a karimba in the key of A, and most of the student karimbas sold by Kalimba Magic are in G or C. Fear not! It makes no difference if you are in F, or G, or A, or C – you accomplish these different keys by moving all the notes up or down by the same amount, so the songs will sound the same, no matter what key you are in (except for the pitch – if you try to sing with the music, you might find one key is too high or another is too low and yet another key is perfect.) You play the songs by playing the same tines, no matter what key the instrument is tuned to. Tine length might be different, as it determines pitch/key (the shorter the tine, the higher its pitch), but the relative tuning is maintained.

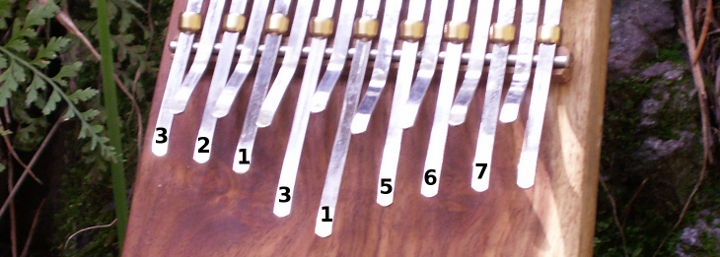

Another way to add tines is to create a whole new row of notes. The 17-note karimba, pictured below, started out like our 9-note student karimba, but then eight more short tines (higher notes) were interleaved between the nine long notes. To make it easier to play these short tines, they are bent upward. In the photo, the numbered tines represent the eight notes of the student karimba/kalimba core/the original mbira. The shorter upper karimba notes were added later in the instrument’s history.

A third way that people added notes to the original mbira was to just stick them in at random. What this does is break up the predictability of the karimba or mbira and it suggests various types of music. The physical arrangement’s irregularity helps slow down the music; it seems to inspire creativity and gives the potential for making more musicical possibilities.

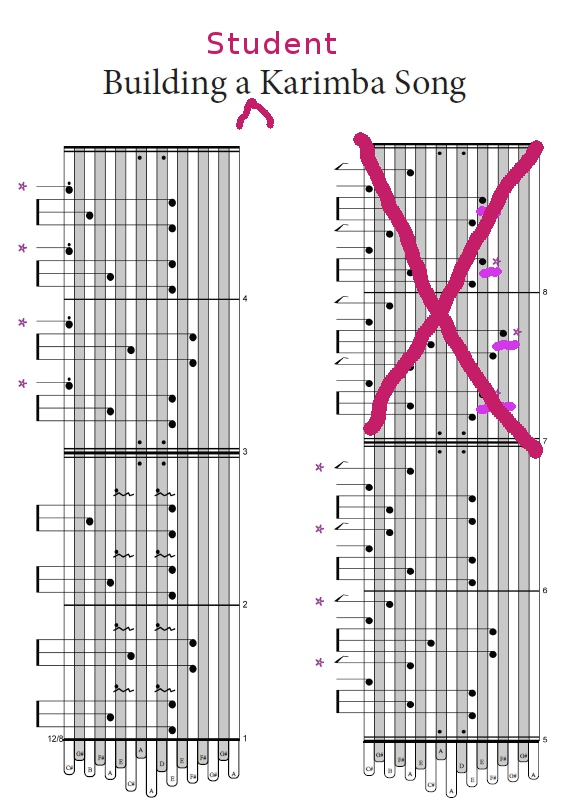

The purple stars in the song tablature (for 17-Note karimba) below indicate notes that are added in each variation. The gray columns represent the upper-row tines of the 17-Note. The first three variations of this song do not use the upper-row tines at all, so you can play them with a student karimba. The fourth variation requires the upper tines, so we cross it out as unavailable to the student karimba.

The first three variations illustrated in the tablature are played entirely on the lower row tines of the full 17-note karimba, meaning you can play these first three variations on the 9-note student karimba, which reproduces the intervals seen on the lower row tines of the 17-note karimba. This is a perfect illustration of what is good about the student karimba.

By the way, the mbira dzavadzimu actually uses all three of the techniques we’ve discussed for adding notes: the central part of the upper row has tines that are related to the student karimba notes, with some added modifications. In the photo, the numbers indicate which of three modification categories those tines fall into. (1) Several shorter, higher-pitched notes have been added on to the left and the right, extending the “wings” by one note on the left and several notes on the right. (2) Another row of extra-long tines has been added to the left side to play bass notes (and the upper left row of tines are bent upward to permit both long and short tines to be easily played). (3) One extra note which was not present on the student karimba was added seemingly at random in the middle of the upper left side.

The mbira dzavadzimu is thought to have evolved from the “kalimba core” – now reproduced as the “student karimba” by adding notes through the three different methods mentioned in the text.

Back to the student karimba, which, as we have looked into, claims to reflect these instruments’ original notes before people started adding onto it many centuries ago. I have worked hard to bring this “kalimba that time forgot” back to life! I have compiled a number of songs, traditional and non-traditional, that work for the student karimba, and I have written up two different books for this interesting, simple, and inexpensive little instrument.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Christmas in July 2025

Christmas in July 2025 Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba

Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba