Use of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.

I have heard from people who were disappointed because they bought “too much kalimba” for themselves – meaning they got more notes than they were prepared to deal with (often, 15 or 17 notes turns out to be too many notes for a beginner). For these people, I recommend they start with a 10-note instrument, as this will be easier to get your head around than the larger kalimbas.

Similarly, when people tell me they are disappointed that their “African” kalimba doesn’t play African music, I point them in the direction of the karimba (yes, with an “R” in the middle, and no, I don’t make these names up myself). And when they find that 15 or 17 notes is too many for them to deal with, I suggest they look into the Student Karimba.

This is a great instrument for children, for adults who may be overwhelmed by bigger kalimbas, and for people who just want a taste of Africa without having to work too hard. (Note: I LOVE to play these instruments myself, and I do perform songs on the Student Karimba. It is a small instrument, but it is also a real instrument.)

I should note that even though there is fair evidence for this being the “original kalimba,” essentially no group of people in Africa make, play, or sell this instrument today. It is like a fossil kalimba that comes from an earlier time. To make the Student Karimba, I convert other 8- and 9- note instruments into the Student Karimba note layout and tuning.

My favorite kalimbas for making Student Karimbas are the Goshen flat boards and the Goshen boxes. The Goshen flat boards are a bit easier to hold due to the thinner body, and they have wider tines, which are easier on the thumbs. The natural key for the flat board karimbas is G (with the low note being G below middle C). The box instruments are a bit louder and higher, and have the sound hole on the front and two sound holes on the side that you can cover and uncover to make the “wah” sound. The natural key for the box Goshen Student karimba is C (with the low note being middle C).

When looking at images of kalimbas, remember that the tine length reflects the pitch the tine will play. Shorter tines play higher notes, and longer tines play lower notes. When you compare the two karimbas in the image above, you immediately see that the Student Karimba’s tines make the same pattern as the African-tuned Karimba’s lower row of tines.

The African-tuned karimba, of course, plays African music. You can stretch it a bit and play something like Silent Night – but it is a real stretch. African music just pours out of it – basically, you twiddle your thumbs on the karimba, and out comes African music.

But not every tine on the African-tuned karimba has the same provenance. The shorter, upper-row notes on the African karimba were added “somewhat” recently… while people probably started adding the upper-row notes many centuries ago, they were still adding notes to the upper row as recently as 1960. But the lower-row notes? Those are the ancient notes, and the old songs all start on these notes.

Using just the lower-row notes, you can play dozens of traditional African songs. But using just the upper-row notes? I don’t think there is a single song that you can play with just the upper row. This really shows us that the lower notes are the main course, and the upper row notes are there to assist the lower row notes.

In fact, the lower-row notes are a complete instrument unto themselves, and as I mentioned before, Andrew Tracey thinks these are the original notes on the original instrument that is over a thousand years old. It took huge detective work to arrive at that result.

In other words, if Andrew Tracey is correct, the Student Karimba is like a living musical fossil, a time capsule bringing melodic, rhythmic, harmonically complex songs that people played a millenium ago in Africa straight to your living room or front porch. In my opinion, Andrew Tracey’s theory is probably mostly correct; maybe one or two notes were different, but I would not be surprised if a thousand years ago, people played very similar music on an instrument very similar to the Student Karimba.

In other words, if Andrew Tracey is correct, the Student Karimba is like a living musical fossil, a time capsule bringing melodic, rhythmic, harmonically complex songs that people played a millenium ago in Africa straight to your living room or front porch. In my opinion, Andrew Tracey’s theory is probably mostly correct; maybe one or two notes were different, but I would not be surprised if a thousand years ago, people played very similar music on an instrument very similar to the Student Karimba.

This is where the mbira revolution started, as metal tines were put onto kalimbas for the first time in southest Africa.

In addition to these assertions, we have the songs the Student Karimba can play. When you hear the depth of these traditional African songs, and realize you are playing them on an 8- or 9-note instrument, you begin to take this instrument seriously. This is, in my mind, the most plausible explanation I have heard for how the African mbira started.

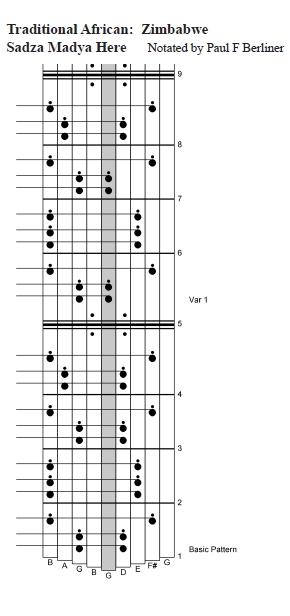

The song “Sadza Madya Here” which was first notated by Paul F. Berliner in his book The Soul of Mbira, has several variations, and most of them can be played on just the lower-row notes. This is a prime example of the kind of music in the books for the Student Karimba.

And the coolest thing? When you get good at playing the Student Karimba, you can take everything you have learned and transfer it to the 17-Note African-tuned karimba – the lower row consists of exactly the same notes you know from the student instrument, and you can add the upper-row notes to songs on your own schedule.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades 8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba

8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and Magic

Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and MagicUse of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.