Use of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.

Sometime between 600 and 1000 years ago in the Zambezi Valley of southeastern Africa, something amazing happened – four-phrase mbira music was born. This revolutionized the music that had been played for a very long time, and greatly increased its sophistication, sort of like going from nursery songs to Pachelbel’s Canon.

The new musical structure was complex enough to support a wide range of songs. In fact, new songs in this vein continue to be created today. There is basically an infinite supply of mbira-type music.

In this post we begin analyzing how new songs can be created within this four-phrase system. One way is to start the song at different places in the cycle. We show you two common places to start, and illustrate the differences in the music.

You will probably want to read Part 1 of this series if you haven’t already, and it is provided as a link at the end of this post.

In 1989, Andrew Tracey (son of Hugh Tracey, who was the father of the modern western kalimba) wrote a seminal scholarly paper called “The System of the Mbira.” The theory that Tracey puts forth shapes current harmonic understanding of most traditional mbira music. It describes the structure from which we can continually create new mbira-like music on any instrument.

I like to think of the mbira cycle as an ever-spinning merry-go-round. There is no beginning and there is no end, and you can get on the merry-go-round anyplace you like.

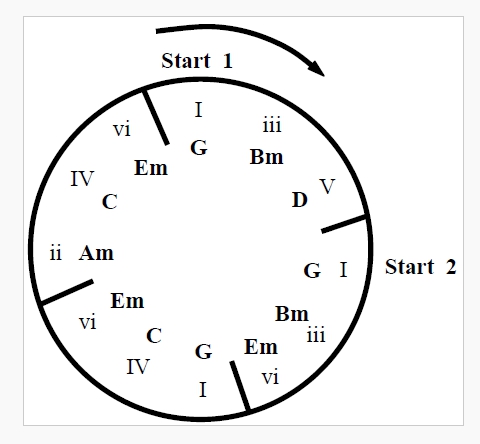

In my explanation of the chord sequence in part 1 of “The System of the Mbira,” I start the sequence at a certain place (“Start 1” in the diagram below). But starting in a different place can make big changes – see “Start 2”. Even though the chords of the entire cycle do not change, where you start can strongly affect the musical feeling evoked.

A song can start anywhere in the mbira cycle. The “Start 1” spot is where I like to start talking about the mbira cycle because it makes the most intellectual sense. However, the “Start 2” spot makes more musical sense to me. Either one is valid.

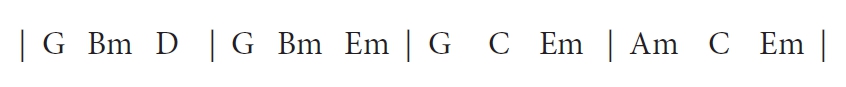

MBIRA CYCLE CHORDS IN KEY OF G STARTING AT “START 1”

If you look back at the diagram at the top of the page, which starts at the “Start 1” point, you can see that the music is moving in an orderly manner from a lower range of notes, gradually, to a higher range. When you click on the “Start 1” sound player above, you can hear the music progressing from the lower “G Bm D” up to the higher “Am C Em.” This transition occurs completely in one four-phrase cycle and returns to the beginning phrase after that cycle ends. The transition’s orderliness, and its logical progression, make sense to the mind and sound good to the ear at the same time.

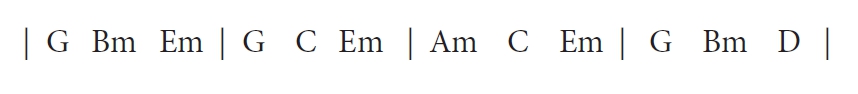

MBIRA CYCLE CHORDS IN KEY OF G STARTING AT “START 2”

However, when you start the cycle at “Start 2,” which is the second phrase relative to the “Start 1” cycle, two different things happen: the opening chords “G Bm Em” support a descending melody line (G F# E – because F# is the 5th of the Bm chord, and of course, G and E are the roots of the G and Em chords respectively). You can hear this high melody line right away in the “Start 2” sound file. Also, if you look at the “Start 2” chords, you see that the last phrase is “G Bm D” – that is, it ends on the D, or V (the five) chord. Furthermore, as the cycle loops around, it starts in the G, or I (the one) chord. This means that the cycle boundary, from cycle end to the next cycle beginning, corresponds with the classical western chord progression of V -> I. In other words, musically, this “Start 2” cycle is much stronger than the “Start 1” cycle. It is interesting that this version of the cycle is much more prevalent in Shona mbira music than the “Start 1” version.

This is how I did it when I was learning this stuff: I learned the “Start 1” version of the cycle for several weeks, and could not even begin to think of the “Start 2” version. However, a friend of mine started playing an mbira song on guitar that was based on the “Start 2” version of the chords. I would start my version on his last phrase, and then on my second phrase he would be starting his first phrase. In other words, at that time I did not understand or hear the “Start 2” version, but I could hang on and play with my friend doing that “Start 2” version by pretending he was starting in a different place.

After many more weeks (or months, or even years…), now I can hear either starting point.

As I’ve said before, this blog post isn’t going anywhere. If you don’t “get it,” go off and think about it and come back and look for this post when you are more ready for it.

Now for a huge philosophical question – if the chords are the same, how does anyone really know if something is starting at “Start 1” or “Start 2”? Is it even a meaningful distinction? Any given piece of music can be heard as starting at either place, but often the player will give musical cues or accents that indicate he or she is really thinking of one or the other as the starting point.

Ambiguity is the strength of this music.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades 8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba

8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and Magic

Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and MagicUse of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.