The mystery of the evolving names of the kalimba

Evidence indicates that in 1950, kalimba and karimba were used more or less interchangeably to describe any traditional African thumb piano. Seventy years ago, mbira dzavadzimu meant exactly what it does now – a particular traditional Shona thumb piano – and the mbira nyunga nyunga probably was not even a thing yet. Seventy years ago was just before Hugh Tracey began to build and sell a new instrument which he called a kalimba, which combined features of many traditional instruments and had a western tuning.

Thumb pianos evolved over time and were affected by numerous influences, ancient and modern, African, European, etc. They have a very rich, varied genealogy. Today, kalimba usually refers to non-traditional thumb pianos. Karimba refers to a particular family of traditional African instruments also known as the African-tuned karimba. Mbira nyunga nyunga, which translates to the “sparkly sparkly mbira” is essentially the same instrument as the karimba, though if it is rustic-looking, it is more likely to be called mbira nyunga nyunga, and a workshop-made instrument might be more likely to be called karimba.

But it isn’t exactly that simple, and here I will outline the details of this fundamental discussion.

- The first thing I notice about a karimba is that some of the tines are bent upward, and it has two rows of tines. What about Sansulas, which also have two rows of tines – are they also called karimba? No – Sansulas are their own things, and to call them karimbas too would be confusing.

- What about the mbira dzavadzimu? The left half of it has two rows of tines, should it also be called a karimba? Again, I would say no – the mbira dzavadzimu is its own thing, and calling it a karimba would not add any clarity.

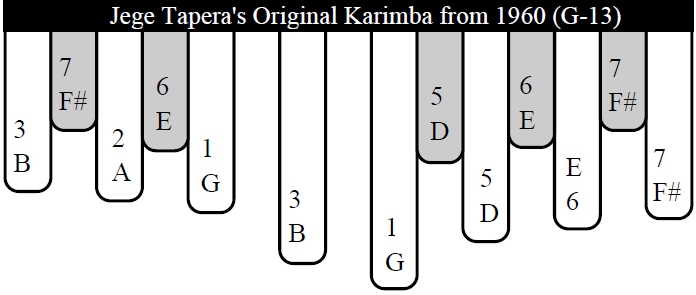

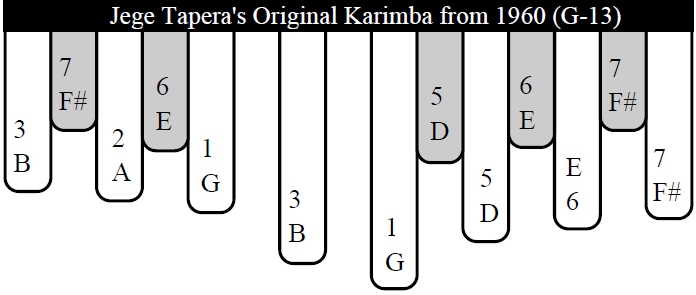

- Regarding the original tuning of the karimba: Andrew Tracey looks back to 1960 when he met Jege Tapera, a master karimba player in Bulawayo, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Tapera played a 13-note instrument in the key of G, and the tuning is shown below. Note that in every tuning diagram, the relative lengths of the tines indicates the tuning – the lower notes are represented by longer tines, and the higher notes are represented by shorter tines. Upper row notes are represented by gray columns in the tuning diagrams:

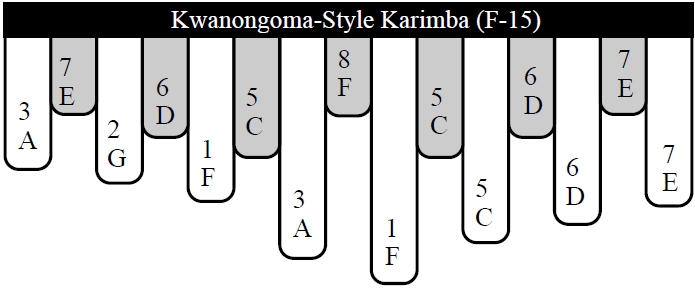

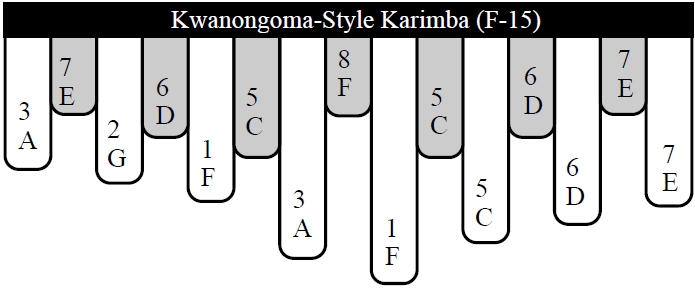

- Jege Tapera’s G-13 instrument became the model for the Kwanongoma School’s program. Two modifications of Jege Tapera’s initial instrument were made: the two central gaps in the upper row of his karimba got another “5” note and a high “8” note; and the pitch of all the tines was lowered by a whole step, so the instrument’s key was changed from G to F. This finalized the 15-note, key of F instrument which was taught at the Kwanongoma College of African Music. Dumisani Maraire learned this instrument at Kwanongoma, and it became his main instrument when he performed in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s. Dumisani appears to be the person who started calling the karimba the mbira nyunga nyunga.

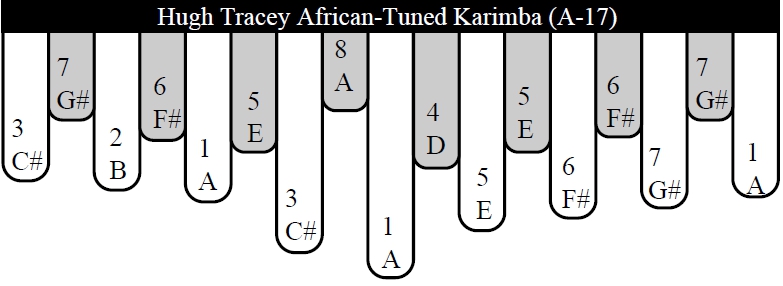

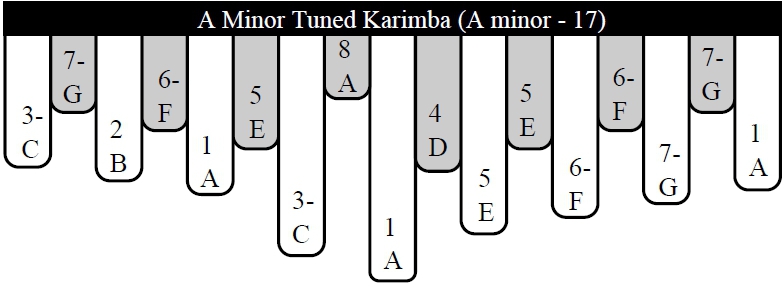

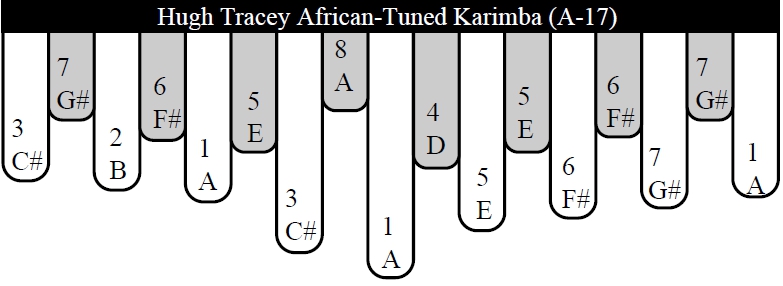

- In the late 1970s, African Musical Instruments (AMI), under Andrew Tracey, started to make the 17-note African-tuned karimba in the key of A, one whole step higher than Jege Tapera’s G instrument. With 17 notes, this instrument had two more than the Kwanongoma Karimba or mbira nyunga nyunga. The added notes are the “4” (D in center of upper row) and another middle “1” (A on the far right). If you focus on the octave pairs made between the upper and lower rows on the right side, you see that on the 17-note karimba, you have to slide off from an upper-row tine to the left to play the same note name on the lower row. On the 15-note nyunga nyunga instrument, you slide off to the right to make the octave pair. I should add that Andrew Tracey told me that such 17-note versions of the karimba with this tuning had been documented by Hugh Tracey’s work, so these extra notes were not just made up by Andrew.

- Why did Andrew Tracey choose to make karimbas with 17 notes instead of 15? The main advantages are that the “4” note (D) gives you a full octave in the upper range of the instrument (the lower octave is missing both 2 and 4), and the doubled A on the far right lets you trill this important note. Adding the “4” note opens up a lot of music to this instrument – notably, the music of the mbira dzavadzimu (a well-known, larger, traditional instrument.)

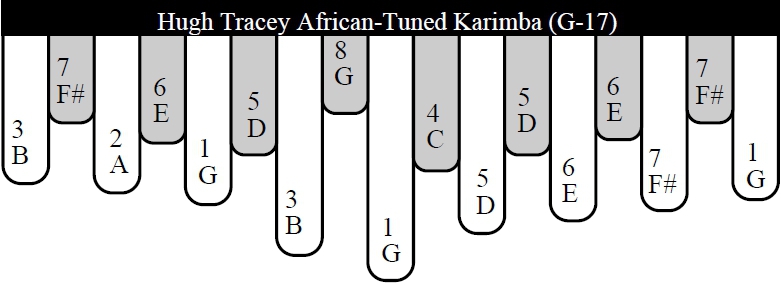

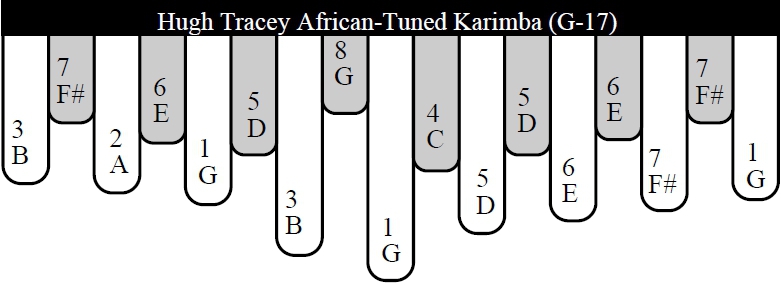

- Most of the other types of Hugh Tracey kalimbas (ie, non-traditional instruments with a single row of tines) are in the key of G. Someone who owns an Alto kalimba or a Treble kalimba would probably want to get their African-tuned karimba in the key of G so they can all play together. Starting with an A-17 karimba, every tine is retuned down / pulled out a whole step, resulting in a G-17 karimba tuning:

- So far, all of these karimbas (G-13, F-15, A-17, and G-17) are functionally related. Don’t look at the note names, but look at the note numbers. The “1” will be right in the center of the low row. To the right of this low 1, the notes go 5, 6, 7. Because these instruments all have their numbers in pretty much the same place, it is easy to see that these four instruments can all play the same music with the same thumb strokes, so they are all karimbas. By the way, that is my most pure definition of the word karimba – a karimba is an instrument that plays karimba music with the same basic thumb strokes as any of the above instruments.

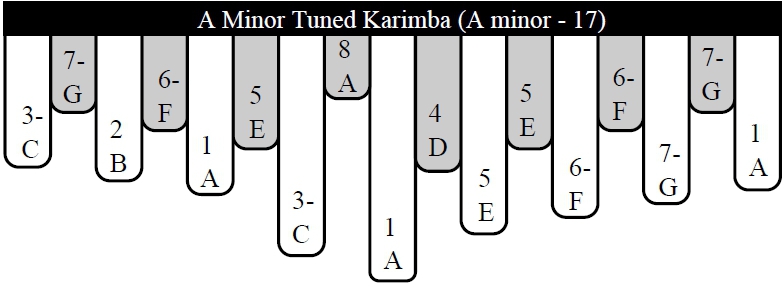

- What about a minor modification of the instrument’s tuning? Will it still be a karimba? I started playing around with minor tunings on kalimbas and karimbas about 15 years ago. To make the natural minor, the 7th, 3rd, and 6th need to be flatted – you can see they have minus signs after them (3-, 7-, 6-) to indicate they are a half step lower than their major interval counterparts. This gives the instrument’s music a mysterious and enchanting quality. Even though the music will sound a bit different in the minor, you still can pluck the same tines and play the same songs… just a bit strange-sounding. So, yes, I would have to call this one a karimba too:

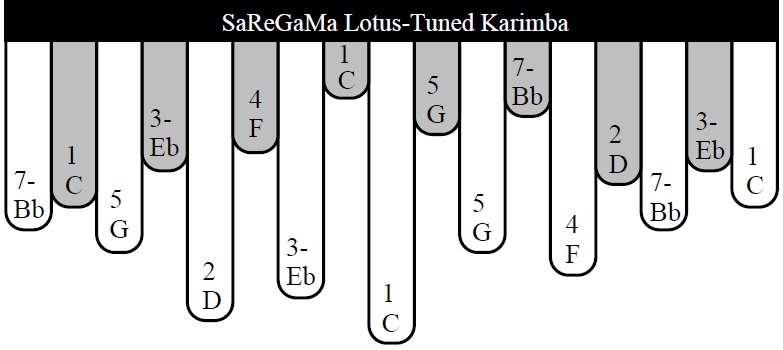

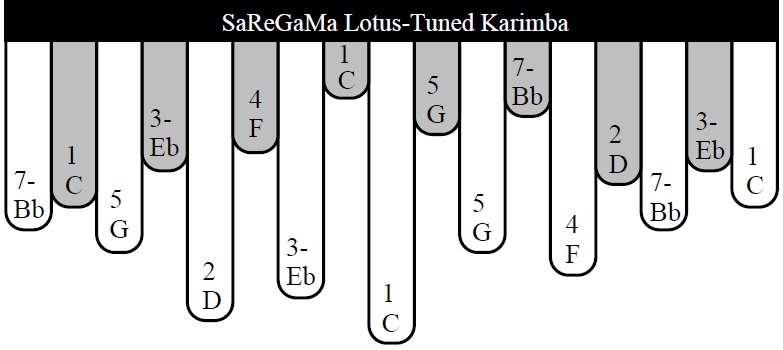

- If the A minor-tuned karimba is still a karimba, can a karimba have any old tuning, as long as half the tines are bent upward? I want to say “no”… but I already said “yes” to this at least once. In 2009, New Age artist SaReGaMa took a Hugh Tracey African-tuned karimba, rearranged the tines, and gave it a totally new tuning. As such, the instrument played totally different music and required very different thumb motions. I had the opportunity to call this instrument something else, but at that time I decided to use “karimba” because it was made from an African-tuned karimba. However it’s not hard to see that the tuning of this instrument is very different, because the tips of the tines trace out a very different pattern:

I have come to regret my choice of calling the “Lotus” a “karimba.” Logically, I think the name karimba should mean both an instrument with a bunch of tines bent upward in a second row, and an instrument with a tuning related to the traditional karimba tuning, so it can play the old traditional songs. However, in practice it is too late, and I also call structurally similar instruments karimba, even if their new tuning prohibits the playing of traditional African songs.

To attempt a few strong statements: I would add that I seldom call any of the above instruments kalimba (unless I am looking at these instruments, with other non-traditional instruments, in the most generic way I can… I might call them all “kalimbas”). My standard usage saves karimba for the family of traditional tunings as outlined above. I do call the Lotus karimba a karimba.

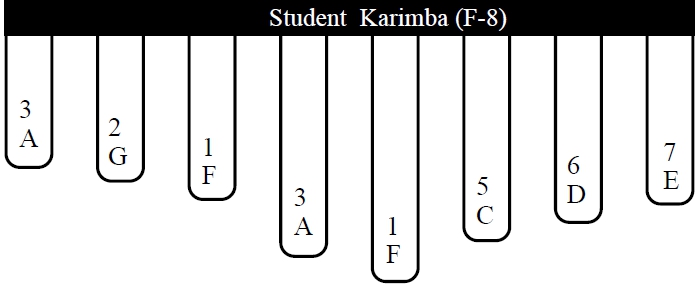

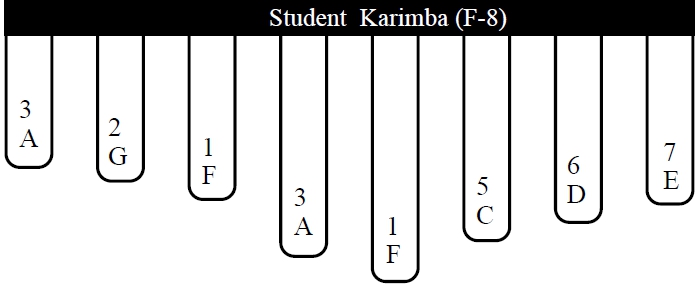

Similarly, I would not pick up any instrument with a single row of tines and call it a karimba… unless of course, it is the student karimba. (No, I’m not kidding… but hear me out, this exception makes sense.)

As I write approximately twice a month, whether I need to or not, Andrew Tracey speculates (with a fair amount of evidence) that many centuries before Jege Tapera had his 13-note instrument, people played similar music on an 8-note version of his instrument. Andrew calls this both the original mbira and the kalimba core. I call it the student karimba, because its notes are the bottom 8 notes of the karimba, it’s a perfect, simple place for anyone to start learning about African music, and everything that you learn on it can be easily translated to one of the bigger karimbas.

Anyway, this article attempts to explain my usage of kalimba, karimba, and mbira nyunga nyunga so you can understand me better. The words you use to describe your own instrument? That is up to you. Choose wisely, have fun, and be open to changing your mind as your understanding evolves over time.

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades 8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba

8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and Magic

Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and Magic