Recently, Lilly wrote to Kalimba Magic:

“I am experienced with reading standard staff musical notation, and I don’t really like the kalimba tablature, and I don’t understand why you use it. Can I just read staff notation with my kalimba? Please give me the main advantage to using tablature to notate kalimba music.”

Yes, Lilly, I think there are some really big advantages to using kalimba tablature rather than staff notation. Consider kalimba tablature to be my chosen way of expressing my 33 years of kalimba-playing experience to you. It is a doorway to my kalimba-playing thought process.

First, it’s good to be clear about these two very different modes of conveying music. Staff notation is a graphical representation of how the music goes (how it sounds).

First, it’s good to be clear about these two very different modes of conveying music. Staff notation is a graphical representation of how the music goes (how it sounds).  Kalimba tablature is a graphical representation of what tines need to be played – exactly how to play the music on kalimba.

Kalimba tablature is a graphical representation of what tines need to be played – exactly how to play the music on kalimba.

Staff notation requires an instrumental musician to interpret first the notes and then apply them to the particular instrument they are playing. Kalimba tablature does not require interpretation; it basically asks that you follow graphical directions only. There are many good reasons why this makes sense for playing a kalimba.

Let’s consider the kalimba as an instrument. While it can play great music, it has some strikes against it: it doesn’t have a very big range (one or two octaves); it is missing several notes in that range (sharps and flats); and, unless it is a rare chromatic kalimba, it plays in just one key.

The kalimba is a simplified instrument. So, consider kalimba tablature to be a simplified notation system that is uniquely suited to the kalimba.

How Much is Certainty Worth?

The main advantage of kalimba tablature: if a song is written down on kalimba tablature for a particular kalimba, you know with absolute certainty that this song can be played on that kalimba. I will convince you shortly that, if you pick a random song written in staff notation, there is a very high probability that you cannot read it on your kalimba, either because the staff music is in the wrong key, or it requires too many accidentals, or it goes out of the range of the kalimba. (For the statistical calculations, see the last section of this article.)

When I make a kalimba instructional book, I deal with all of these issues, and essentially make them go away. I transpose the song to the kalimba’s natural key. If there are too many accidentals, I will bypass that song. If there are just a few accidentals, I can finess them in various ways and make an arrangement that works for the kalimba. And of course, I make sure the song doesn’t require any notes lower or higher than what the kalimba has. Or, if the song requires those extra high notes, I will alias the melody down an octave, or otherwise adjust the song to make it work on this particular kalimba.

Each type of instrument is unique in its voice, abilities, and proclivities. Yes, you can read music written for flute or piano on kalimba (and more on this later), but these tunes will not draw on the voice and natural strengths of the kalimba.

Now, please consider my kalimba tablature. I invented it for my kalimba students. It is a very simple, but easily recognizable map or graphical representation of the tines of the specific type of kalimba you have. Each kalimba will have slightly different tablature, to account for the number of tines, which ones are painted, how they are tuned, and whether some of the tines are bent upward or not. If you have tablature that is right for your kalimba, there is a one-to-one correspondence between the columns of tablature and the tines on your kalimba, and there is a 100% chance that this song can be played on your kalimba, without any modification.

If you are able to read and use staff notation, you know it is a two-step process – you need to first recognize the note or notes the staff is referring to, and then you have to translate that note to the proper tine on the kalimba. (And as you now know, with staff notation, there is never a certainty that this specified note will actually be on your kalimba, but when you make sure it really is, you then play it.) This is great for accomplished musicians. If this is you, go for it!

But I am the musical apostle to the people who never imagined they could play music, or who have owned a kalimba for 30 years and always thought they should be able to play, or the person who is playing at Level 1 and dreams of someday playing at Level 5. My kalimba tablature gives them a doorway into musical accomplishment that they never imagined was possible for them. There is a direct and immediate mapping from kalimba tablature to kalimba. You can see the geometrical patterns your thumbs will need to make to accomplish the music. Playing the kalimba is about the physical patterns your thumbs need to make – like dance steps. And the tablature reflects the dance steps.

I think that the benefits of using tablature are clearly obvious. People with no musical experience can read kalimba tablature with minimal stress. It is much more accessible than staff notation, making it easier and more likely that more people will be able to use and derive joy from kalimbas.

Shortly after I invented my kalimba tablature in 2004, I taught kalimba to a class of eight 1st and 2nd graders in a weekly afterschool program. Even though the first targets of my kalimba tablature were teenagers and adults, I found that every one of these 6, 7, and 8 year olds, who had no prior experience reading music, had successful experiences reading tablature. They were even able to start doing simple harmonies and even counterpoint.

I have found that it is the people who have extensive musical experience, and thus strong habits connected to reading music, who resist kalimba tablature. And it’s true, reading standard musical notation is a language some people learned very early and have used all their lives, and to jump into a completely new language may be a bit of a shock.

Even though the tablature is very simple and relatively easy to read, it is also very powerful. As I expressed already, the tablature can be modified to cover any sort of kalimba that I have come across. The tablature can handle any rhythm (the notation rules are actually the same as for staff notation), and any chord or combination of multiple tines. The capability of tablature encompasses chords, rests, melodies, harmonies. All you have to do is get used to reading the notes UP the page instead of across the page.

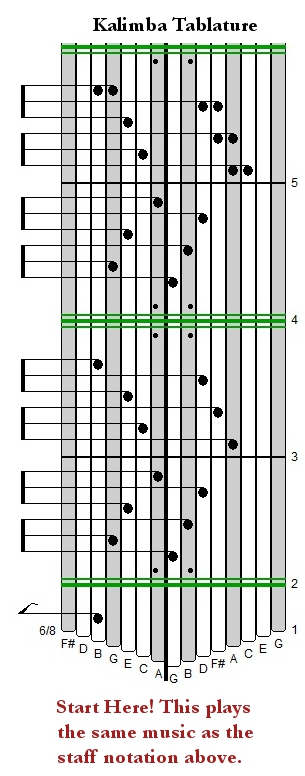

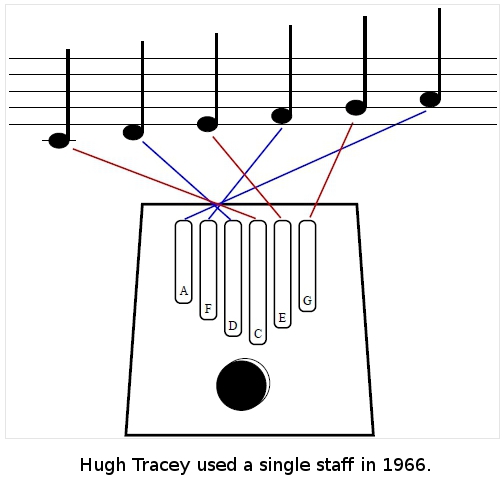

When I started thinking about the optimal way to notate kalimba music, I decided to look at what other people had done. Hugh Tracey and his son Andrew had made a 16-page kalimba guide in 1966, and single-staff notation was used. This put both the left and right thumb on the same staff, which was confusing, and it seemed to me right away that a single staff for all the music was not the best approach.

When I started thinking about the optimal way to notate kalimba music, I decided to look at what other people had done. Hugh Tracey and his son Andrew had made a 16-page kalimba guide in 1966, and single-staff notation was used. This put both the left and right thumb on the same staff, which was confusing, and it seemed to me right away that a single staff for all the music was not the best approach.

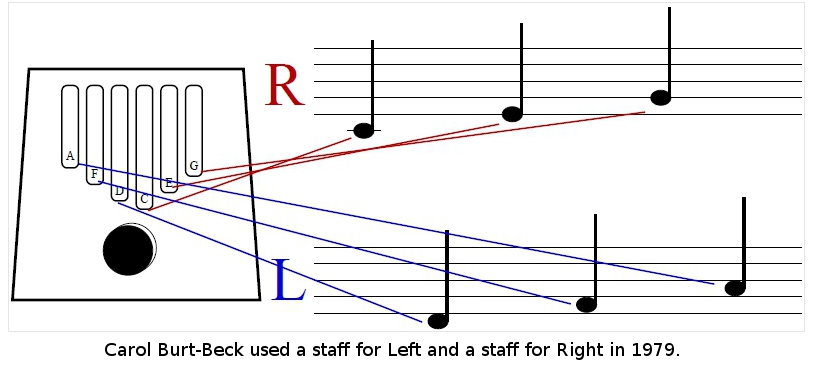

In 1979, Carol Burt-Beck published a book called “Playing the African Mbira” which used staff notation. (The book’s title was a misnomer, in that it offered instruction on both the Hugh Tracey Alto and Treble kalimbas [the two main commercial kalimbas at the time], but not the mbira.)

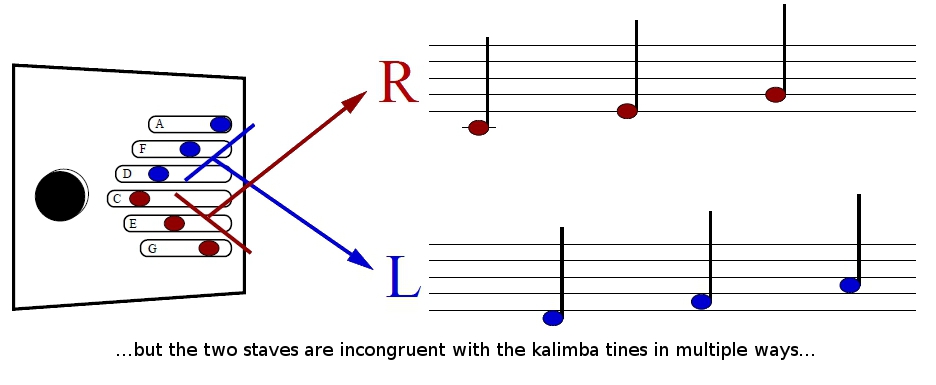

In her book, Carol Burt-Beck introduced her original kalimba notation conventions. I worked with this system to understand and use it. An important thing that I feel she got right was that she separated the two thumbs onto different staves, just as they do for piano. On piano, the lower staff, or the left hand’s staff, is in bass clef while the right hand’s staff is in treble clef. On the kalimba, the left thumb and right thumb staves are both in treble clef, because the two thumbs have essentially the same range. Furthermore, the right thumb plays every other note on the staff – corresponding with the lines on staff notation – and the left thumb plays the other notes – equivalent to the spaces on staff notation. That seemed a bit wrong to me, that it would be really easy to write a note on the right thumb’s staff that was not on the right side of the kalimba.

Which points to my big complaint with this system: it was not congruent with the kalimba… in three ways! First and most obvious to me: when you hold the kalimba, the tines are parallel to lines that run up and down the page, while staff notation runs from left to right across the page. OK – so bear with me here: if I take my kalimba and rotate it 90 degrees (as in the above diagram), now my tines are parallel with the staff. But when I do this, my right hand is hovering over the lower, or left thumb’s staff. And my left hand is hovering over the right thumb’s staff. My mind has to make the crossover. Further – if I play a left-thumb arpeggio, that thumb’s motion will be parallel with the motion of the notes on the staff notation (both going up the page in this illustration)… but if I play an arpeggio with the right thumb, the physical motion of the thumb will be opposite the symbolic motion of the notes on the staff (on the kalimba, the notes go down the page, while on the staff, the notes go up the page).

Which points to my big complaint with this system: it was not congruent with the kalimba… in three ways! First and most obvious to me: when you hold the kalimba, the tines are parallel to lines that run up and down the page, while staff notation runs from left to right across the page. OK – so bear with me here: if I take my kalimba and rotate it 90 degrees (as in the above diagram), now my tines are parallel with the staff. But when I do this, my right hand is hovering over the lower, or left thumb’s staff. And my left hand is hovering over the right thumb’s staff. My mind has to make the crossover. Further – if I play a left-thumb arpeggio, that thumb’s motion will be parallel with the motion of the notes on the staff notation (both going up the page in this illustration)… but if I play an arpeggio with the right thumb, the physical motion of the thumb will be opposite the symbolic motion of the notes on the staff (on the kalimba, the notes go down the page, while on the staff, the notes go up the page).

So you see, when I try to follow Carol’s two-staff system, I find that my brain has to work very hard, in multiple dimensions, at untangling and transposing and reflecting all these different motions. It was just not natural for me. Sure, I could learn to do this, but would it ever feel right to me?

After a few weeks of trying to work within Carol Burt-Beck’s system, it occurred to me that I could untangle all of these incongruencies if I redesigned the staff system just a little bit.

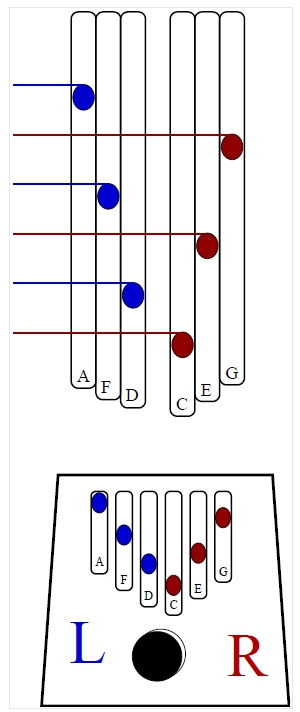

First, I kept Carol’s two-staff system. I found it was very useful to specify in one region what the left thumb is doing, and in another region what the right thumb is doing. However, in Carol’s system, there is nothing to prevent notating something on the right staff that can only be played on the left tines, and vise versa. So, instead of a symbolic system that had the flexibility of telling your right thumb to play a note it didn’t have access to, I wanted a more concrete representation of the actual kalimba tines.

First, I kept Carol’s two-staff system. I found it was very useful to specify in one region what the left thumb is doing, and in another region what the right thumb is doing. However, in Carol’s system, there is nothing to prevent notating something on the right staff that can only be played on the left tines, and vise versa. So, instead of a symbolic system that had the flexibility of telling your right thumb to play a note it didn’t have access to, I wanted a more concrete representation of the actual kalimba tines.

That’s it! I made a drawing of the left tines, and a drawing of the right tines, separated by a little gap. The diagram resembled the kalimba, but the tines were further stretched up the page. I placed note symbols on the columns representing the tines, to indicate which tines should be played in which order. There is no mental transformation required. I just saw a note on my “tine map” and played the corresponding tine.

And oh – instead of running these new tine diagrams across the page, I wanted them to be clearly echo the reality of my kalimba – and made the tine diagrams parallel to the kalimba tines, running up and down the page.

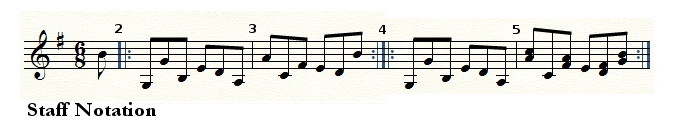

But, I pondered: should the tab read UP the page, or DOWN the page? I made the tab run UP the page. And if you rotate the tablature 90 degrees clockwise to mimic the orientation of staff notation, all the note flags and everything map perfectly into what you expect to see.

Sometimes, when I am reading the notes off the tablature, gazing slowly up the page, I imagine that I am playing Packman in 1980. I am going up the page and eating the notes right off the page as I go.

The final step in my transformation from staff notation to tablature: The Hugh Tracey kalimba has one out of every three tines painted to help you keep your place on the kalimba and to help you relate the left side and right side tines to each other. Similarly, if the tablature was not marked in some way, you would not be able to keep your place on the tablature when there are many tines on each side. So, whenever there is a painted tine, the corresponding column in the tablature would be shaded to facilitate transferring the note from the tab to the kalimba.

The final step in my transformation from staff notation to tablature: The Hugh Tracey kalimba has one out of every three tines painted to help you keep your place on the kalimba and to help you relate the left side and right side tines to each other. Similarly, if the tablature was not marked in some way, you would not be able to keep your place on the tablature when there are many tines on each side. So, whenever there is a painted tine, the corresponding column in the tablature would be shaded to facilitate transferring the note from the tab to the kalimba.

I made my very first kalimba book, “Alto Fundamentals,” in 2005. And I made the tablature “by hand” – literally! I used blank tablature printed out from a graphics program, and I used a special Pentel pen to create the notes on the blank tab. I then scanned the pages and inserted those images into the document on my computer to make the first PDF for the book.

Obviously, I needed to look into another approach at implementing my new Kalimba Tablature!

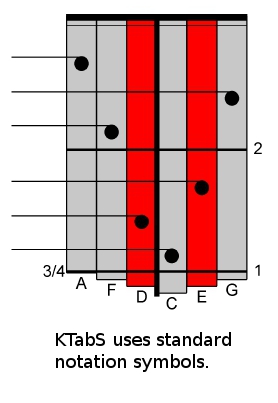

What really enabled me to become a kalimba-book-making machine was a program called KTabS. In the spring of 2006, Sharon Eaton bought a Treble kalimba from Paul Tracey, Hugh Tracey’s younger son. She went online to look for kalimba books and found Kalimba Magic right away and bought the Treble Fundamentals Book. And within minutes of receiving it in the mail, she asked her husband if he could write a program to implement my kalimba tablature. They named the program he invented “KTabS” (kalimba tablature software), and it became a robust and highly capable program for inputting, editing and printing high quality kalimba tablature for essentially every type of kalimba.

I have to say that the KTabS program is a joy to work in. Perhaps the most important aspect of KTabS is that you can play the music you have created back and hear what it sounds like. You know what you wanted it to sound like. If the music you captured on the tablature is correct, it will sound correct. If it is incorrect, you can hear that right away. So, it is also an invaluable composition tool. Yes, it’s a computer program and not given to memory lapses or distractions or mistakenly putting a dot on a wrong tine.

I have to say that the KTabS program is a joy to work in. Perhaps the most important aspect of KTabS is that you can play the music you have created back and hear what it sounds like. You know what you wanted it to sound like. If the music you captured on the tablature is correct, it will sound correct. If it is incorrect, you can hear that right away. So, it is also an invaluable composition tool. Yes, it’s a computer program and not given to memory lapses or distractions or mistakenly putting a dot on a wrong tine.

KTabS is an impeccable accuracy checker too. (Confession time: In my very first book, I actually made several errors. I notated, by hand, incorrect tines, and I didn’t even realize this until after I printed the book. I can say that since adopting KTabS in the summer of 2006, I have had an ironclad check against incorrect notes.) If you see a note on a tine in kalimba tablature in one of my books, you know that I meant for that note to be there. Having made many errors in the past, this is something that gives me a great amount of reassurance, and it should give you confidence in the accuracy of the tablature.

I estimate that something between 85% and 99.8% of all staff music is not appropriate for your kalimba. This assumes you do not have a chromatic kalimba, but the more common type that plays the simple “Do Re Mi Fa So La Ti Do” scale.

First we look at the key. There are 12 different keys. Now, there is a lot more music written in the key of C than in the key of F#. But even if you have the most common key, still something like 80% of staff notation music will be written for keys other than yours. There are collections of simple piano tunes in C, and you may want to check them out… but there will be other problems making them ill-suited for kalimba.

Next is accidentals. An accidental is a note that is not in the key, which means it’s not on your kalimba. Folk tunes and modern pop songs often do not have accidentals. Classical music and jazz have lots of accidentals. SO, it depends on what kind of music you are looking at. For more “vanilla” musical styles (folk and pop), maybe you only lose 10% of the music because it has accidentals. For classical or jazz, it may be close to 80% or 90% of staff music that cannot be played on the kalimba due to the lack of accidentals.

And finally, the limited 1-2 octave range of the kalimba will restrict your use of staff music. There are many instruments that have a 2-3 octave range, like flute, trumpet or voice – but these are all single note instruments (they can only produce one note at a time). Guitar, violin, and marimba have more like a 3-4 octave range. Piano has a bigger range yet. To find a song that fits into the small range of the kalimba you have to get lucky. The best place to look is elementary flute, voice or trumpet music.

Yes, simple songs for some of these instruments will generally fit on the kalimba. But most interesting music will have problems in that it will have notes that are higher or lower than the high and low notes of the kalimba. Again, it depends on what library of music you are digging through, but range limitations will eliminate between 20% and 90% of the staff music you might look to play on kalimba.

Basically, not a lot of music works for the kalimba without modification, so it’s really wonderful to get music made just for it.

As a math wiz, I will, without much explanation, calculate an upper estimate of how much staff music might be appropriate for the kalimba: (1 – 0.80) * (1 – 0.10) * (1 – 0.20) = .144 – which means that 85.6% of staff music (easy songs for flute, say) would be inappropriate.

For the lower limit of how much music is appropriate: (1 – 0.80) * (1 – 0.90) * (1 – 0.90) =.002 – which means that 98.8% of staff music (say jazz for guitar and piano) is not appropriate for kalimba.

On the other hand, if you restrict yourself to a recorder songbook in C, you will be able to read all the songs. But if you learned kalimba from a recorder song book, you would be missing the magic of what makes a kalimba… a kalimba.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Christmas in July 2025

Christmas in July 2025 Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba

Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba