Are you having difficulty understanding note and timing symbols in the tablature?

This blog post is just for you – it’s the second of our series on learning how to read kalimba tablature. In the first post, we talked about what the “tine map” means, looked at the different types of notes and how long each kind lasts, and introduced how to understand timing and keeping time.

This installment of the multi-part series on reading tablature covers the details of the “tie” symbol (a sideways smile) and the “dot” (a dot immediately after – or “above” – any note symbol). Both the tie and the dot modify the length of the notes they are applied to, resulting in note lengths that we could not indicate using just the basic note types and increasing greatly how music can be communicated using a visual system.

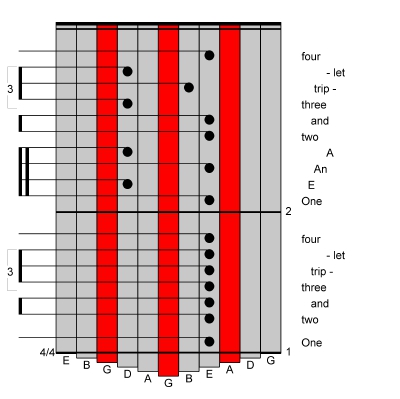

When you look down at the bottom of tablature that is specific to your kalimba, you see the shape of your kalimba’s tine ends, represented by the tab columns. Each tine is labeled with the name of its note. This is a simple map to your kalimba’s tines. But to really be able to read tablature, you need also to see that it is a map in time. The bottom of the tablature is also its beginning.

The song begins down at the bottom of the tablature column. Time in this map runs from bottom to top. As you go up, you are looking at the song later in time, much as standard musical notation runs from left to right.

In an earlier post we showed how the whole note gets 4 beats, the half note gets 2 beats, the quarter note gets 1 beat, and the eighth note gets 1/2 of a beat. What if we want a note that is to be held for 5 beats, or 1 1/2 beats? How do we make a note that lasts for this long?

In the tablature examples below, we provide sound recordings in which there is a full measure “count off” before the music starts playing, and then we “count” the rhythm as the notes are played; this is also spelled out to the right of the tablature.

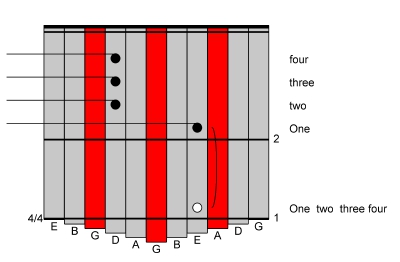

Two or more notes connected with a tie are played as a single note that lasts as long as all of the tied notes combined. The tie here is the curved line in measure 1 which can be seen on the red column (the “A” tine) and it binds the two notes so they are played as one.

The whole note in measure 1 gets 4 beats, and the quarter notes in measure 2 each get 1 beat. The tie joins the whole note together with the first quarter note, and the new composite note lasts a total of 5 beats.

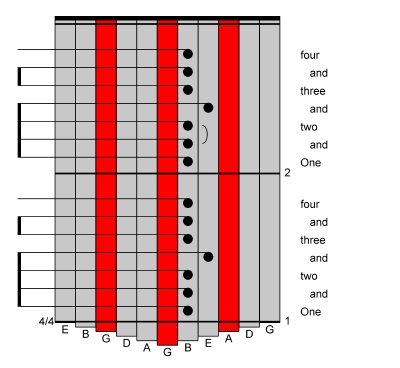

The rhythm in the first measure is very straight: “One and two and three and four – ” – or perhaps “I can jump up on the bed”. In the second measure we have tied the second and third eighth note to each other, counted as “one and-two and three and four” where the “and-two” makes one longer beat – or “jump UP – upon the bed.”

The tie joins two eighth notes, each lasting half a beat, making a single note that is held for a total of one beat. Interestingly, this tied note starts on the off-beat (on the “and” just after the “one.” When you get to the next down-beat on “two,” no note is played (in the recording, you can hear this “naked 2 count”). When you play on the off-beat and don’t play on the down-beat, you likely have syncopation.

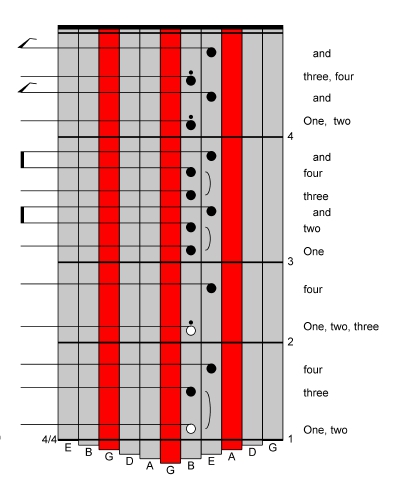

The tie in measure 1 combines the half note (2 beats) and quarter note (1 beat) to create a single note that lasts 3 beats. Measure 2 creates the same music with different notation – the dot immediately after (above) any note will add 50% to the length of the note. As the note in measure 2 is a half note getting 2 beats, the dot instructs us to add 50% of 2 = 1 to the length of the note, for a total of 3 beats.

Measures 3 and 4 illustrate the same concepts, but the notes are coming twice as fast. The tie between the quarter note (1 beat) and the eighth note (half a beat) in measure 3 results in a single note getting 1.5 beats. Similarly, the quarter note with the dot after it in measure 4 – called a dotted quarter note – gets 1.5 beats.

These dotted quarter / eighth note figures create a lopsided feel, with the emphasis placed on the long first note, and a lighter touch on the short following note. Another way to think about this is that the short eighth note is a lead-in to the following dotted quarter note.

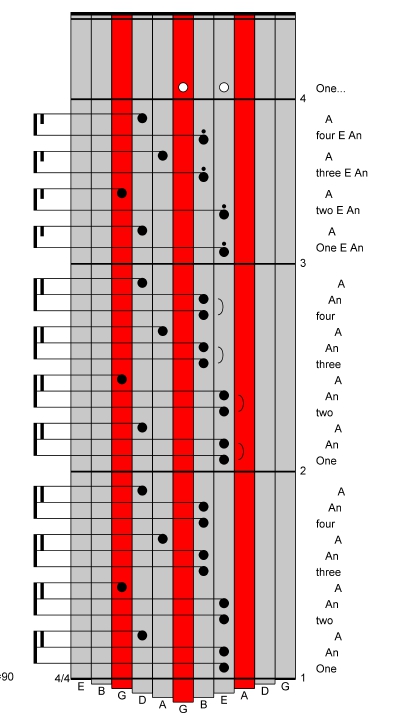

In this example, every group of notes that is beamed (connected at the left edge of the tablature) together gets a total of 1 beat. In measure 1, there are four groups of three notes beamed together – an eighth note getting 0.5 beats, and two sixteenth notes each getting 0.25 of a beat. This is counted as “One and-a two and-a” – or as we write it here, “One An-A two An-a…”

In measure 2, we create a single note out of the eighth and the first sixteenth notes by tieing them together. That tied note lasts 0.5 + 0.25 = 0.75 of a beat, and it is followed by a sixteenth note to make up the remaining 0.25 of the beat. The first note lasts 3 times longer than the second note. This lopsided pairing of notes can make the music feel as if it is galloping.

In measure 3, we create the exact same rhythm by using the dot instead of the tie. The eighth note gets 0.5 of a beat. The dot adds another 50% to the length of the note, which is 50% of 0.5, which is 0.25. Hence the dotted eighth note gets 0.75 of the beat, with the following sixteenth note making up the remaining 0.25 of the beat.

The “dotted eighth / sixteenth” is a very common rhythmic figure in music, and you should learn this and take it with you.

In this example, each group of connected, or “beamed” notes, fills one beat, just as the quarter notes do. Two eighth notes get one beat. Four sixteenth notes get one beat. And if we want to fit in three equal-length notes into a beat, we have what is called a triplet. Triplet notation is three notes with a “3” to the left.

What if everything in a song were based on triplets? We could write it out in the standard 4/4 time signature and write each triplet out with the “3” on the left side. But there’s an easier way.

The “6/8” fraction in the lower left corner is called the “time signature.” Common Time is “4/4” – the first (top) “4” means there are four beats in each measure, and the second (bottom) “4” means the “4th note” – or quarter note – gets one beat. The “6/8” time signature means that there are six beats in each measure, and the “8th note” – or eighth note – gets one beat. That means that six eighth notes will fill a 6/8 measure.

The music is more easily read if we beam the eighth notes together, but it is a convention to not beam across the middle of the measure. This means that in 6/8, the eighth notes are beamed in sets of three. And since we are in 6/8 time, the little “3” at the side of the beam of a triplet is not required, as the triplet is a normal part of this time signature; in the 4/4 time example above, a triplet is not expected or normal so it does get the “3” designation.

The dotted eighth notes in measures 2, 3, and 4 each get three beats, or half a measure.

Sometimes 6/8 is counted in other ways, and we’ll cover that later.

We’ll come back around in the very near future and look at different time signatures, rests, and other complicating factors.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Christmas in July 2025

Christmas in July 2025 Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba

Patriotic and American Music for Kalimba