Use of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.

The kalimba, as most of us know it, is a new adaptation of the family of African lamellophones that includes the mbira and the karimba. As such, the kalimba doesn’t really have a tradition in Africa. This is the very reason I am attracted to the instrument. Without a specific African tradition, we are free to create our own new and evolving kalimba styles.

On the extreme opposite end of the “tradition” spectrum from the modern kalimba is the mbira dzavadzimu, or simply, “mbira”. The mbira’s traditions are strange, quirky, amazing, wonderful, and sometimes downright bizarre all at the same time. One aspect of the mbira’s tradition that is never heard in kalimba playing is the doubling of parts in the melody. The leading line is called kushaura, and following line is the kutsinhira. I invite you to peek inside the amazing world that results when these two parts are put together.

Mbira music is meant to be played by two players, a leader (playing the kushaura part) and a follower (playing the kutsinhira part). The two lines are separated in time by an eighth note. Though sometimes the kutsinhira part strays from the original kushaura part, the two parts are usually similar or even identical, so it sounds like a slap-back echo, or digital delay in modern-speak.

While a single kalimba player is sort of the comfortable norm, a single mbira player is only half the story and is typically never heard. The two mbira parts fit together like tongue and groove, like lock and key. When the two mbira parts are playing together, the music seems to come alive and a 3-D pattern jumps out of the speakers and dances around the room as the two parts pull and push, lock together and unlock.

When the kushaura and kutsinhira parts are locked-in, they make the music very strong and sturdy.

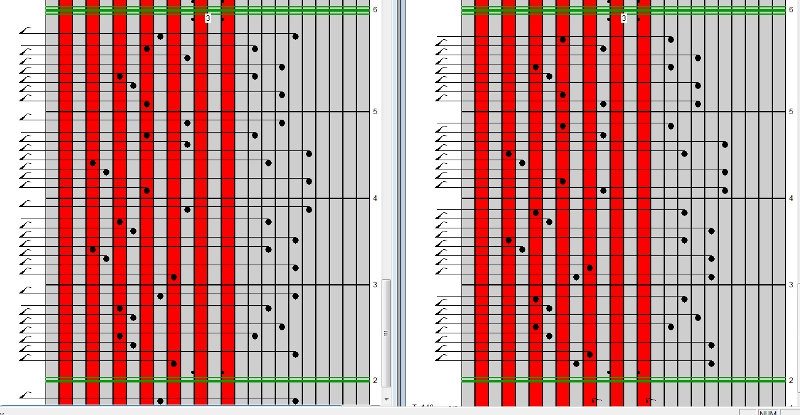

In the mbira song “Kuzanga,” the kushaura and kutsinhira parts are exactly the same. The kushaura part, on the left (in the tablature above, as well as in the left speaker) starts with a pickup. In the recording, the kushaura part runs through an entire cycle by itself before the kutsinhira part comes in. The kutsinhira part, on the right, can be seen to have the same notes, but the pickup now has a rest, and the two notes that were the pickup in the kushaura part have been shifted to be on the first beat of the first measure.

The second to the last note in each measure of the kushaura part (on the left) is a quarter note. There is no flag on the left side of the mast to make this note last longer, as there is with the shorter eighth notes. This leaves a sort of gap in the music. You can hear this gap clearly at the beginning of the recording. As soon as the kutsinhira part comes in, that gap is filled by a note in the kutsinhira part. The kutsinhira part’s last note in each measure is similarly a quarter note, and its gap is filled by the pickup note to the next measure in the kushaura part. This locks the two parts together.

The two players learn exactly how their parts fit together, and if one or the other of them falters a bit, speeds up or slows down, this tugs on the way the parts fit together. The interplay of the parts either pulls the wayward player back in line, or pulls the other player along with the drifting one. It is quite a bit like corrugated cardboard, which is much stronger than single-ply cardboard.

Another key aspect to playing these two parts together is that it makes the music shimmer, as if you are “hearing” a mirage. Your mind gets a bit confused, and you can’t really tell exactly where your reference point is. You have two parts, each competing for the “one” spot – the start of the phrase. As it is uncertain exactly where the “one” is, your mind will hear the music differently than if there were only one part. Different lines jump out that you have never really heard before. It is a pretty amazing feeling to have these musical lines simultaneously shimmering and undulating together, like taking a drug that confuses the senses on the one hand and heightens them on the other. (Unlike some substances that alter the user’s perception, the mbira is not regulated by the government, and unless you are playing while operating a motor vehicle, it’s completely legal. And playing mbira has not been found to be harmful to your health either. Research would probably find it to be very good for you!)

I have been going crazy on mbira for the past three months, but I was not at all prepared for the extraordinary experience of playing both the kushaura and the kutsinhira parts for the song “Kuzanga”. The below recording is my first attempt at putting kushaura and kutsinhira together, and let’s just say my mind is blown! I am thrilled to be at the threshhold of a new universe of music and possibilities!

The following is very important to know if you ever want to record two tracks of the same instrument. It’s a list of tips that came out of my years of playing and recording my own work.

I have exactly one good mbira dzavadzimu, and I have used it for both the kushaura and kutsinhira parts in the recording you will hear. Because of this, I really wanted to differentiate the sounds of the two parts. The first thing I did was to pan the kushaura part over onto the left part of the sonic field (you can hear it more in your left headphone speaker). The kutsinhira part is panned over to the right. The sonic field thus reflects the image of the tablature shown above. To further distinguish between the two, I have the kutsinhira part come in later and go out earlier. What’s more, I have actually totally removed my mbira’s tiny buzzers for the kushaura part and replaced them for the kutsinhira part, and, finally, I used different dezes (gourd amplifiers) for the two separate parts. The sounds of the kushaura and kutsinhira parts are markedly different even though they were played on the same instrument.

All this effort is important because it helps the listener hear what is going on in a complex aural presentation. It’s magical, but it is not magic. You should be able to understand it. Even though the exact same player, on the exact same mbira, made the two tracks, I worked hard to create the illusion that there are two different mbira players, each locked into the groove with the other, living and breathing their beautiful music together.

What comes next? I obviously need to do this with another human being. I need to work some variations into the scheme. Perhaps I need to rewrite the kutsinhira part to dance better with the kushaura part. And I need to get better with my timing – which I think will naturally happen when I add a real human to the mix. Finally, songs such as this one can also be played on the Alto Kalimba, so I should soon be creating kushaura and kutsinhira parts for the Alto Kalimba tradition. And I think I should see about the African Karimba, which also has the capability to be used in this kind of collaboration.

Click the media player below to hear the song “Kuzanga” played on mbira. The left side has the kushaura (leading) part while the right side has the kutsinhira (following) part.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Use of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.

Notifications