Use of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.

Most “primitive” music is so-called “two-phrase” music – basically a call phrase and a response phrase, or a question and an answer. This simple musical form exists across cultures, in nursery rhymes, and in basic karimba music.

Sometime between 600 and 1000 years ago in the Zambezi Valley of southeastern Africa – let’s suppose during the peak of the “Great Zimbabwe” civilization – an incredible innovation occurred: that primal two-phrase tune pattern evolved into a “four-phrase” pattern. This innovation was momentous. Doubling the length of the original two-phrase cycle had the effect of expanding the possibilities of the music by far more than a factor of two. This four-phrase musical structure is the essence of the sound of the mbira. It is one of the pinnacles of African music, culture and intellect.

In this post I will impart my conceptualization of an essential African musical form to you, and will start with the basic chord progression common to a lot of four-phrase mbira music. This harmonic understanding, which can be applied to any instrument, will be demonstrated on guitar in the keys of G and A.

In 1989, Andrew Tracey (Hugh Tracey’s son) wrote a scholarly paper called “The System of the Mbira.” The theory that Tracey puts forth shapes our harmonic understanding of most traditional mbira music. It describes the structure from which we can continually create new mbira-like music on any instrument. As such, it is well worth learning.

In the music that is playing now you can hear the chords of the mbira cycle, played on the guitar in the key of G. If you have a Hugh Tracey Alto or Treble kalimba in G, go get it and try playing along. If you have a karimba in A, there is a link at the end of this post for a sound file with the mbira cycle chords in the key of A.

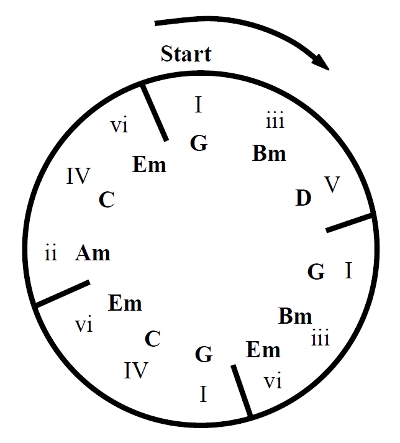

The image above shows the basic form of the mbira system – or mbira cycle, as I often call it. Each of the colored dots actually represents an entire chord, and the note the dot falls on (Do = 1, Re = 2, etc) is the root note of the chord. The entire cycle is made up of four phrases, and each phrase is made up of three chords. When you get to the end of the fourth phrase, you jump right back to the start of the first phrase without dropping a beat – that is, you loop it.

The chords from one cycle to the next evolve gradually – Phrase 2 has the same chords as Phrase 1, except for the third chord which has been raised by a step in the scale (from 5 to 6). Phrase 3 is related to Phrase 2 in a similar way, with the second chord raised by a step in the scale (from 3 to 4). Phrase 4 is related to Phrase 3 in a similar way, with the first chord raised by a step in the scale (from 1 to 2). By the time we are playing the fourth phrase, each of the three chords has been raised, and it looks like we have nowhere to go. But then the cycle is completed when you go from Phrase 4 back to Phrase 1, and each of the three chords drops down by a step in the scale – so “2-4-6” drops back to “1-3-5”.

Each of the four phrases has the same basic upward motion – can you hear that in the recording? It even creates the illusion that the succession of chords is always moving upward from one phrase to the next.

The graphic below makes the cyclic aspect of the mbira chords more explicit. Each of the four phrases lies between the short straight dividing lines. The chords are indicated by name here, for playing on an instrument in the key of G.

Another way to look at the chords of the mbira cycle, with the chords in the key of G. We will use this representation in future posts.

G is a good key for illustrating the mbira’s chord cycle, in part because that is the standard tuning in which many Hugh Tracey kalimbas come to you, including both the Alto and the Treble kalimbas. You can even tune your African-tuned karimba down to G. The key of G is also a generally useful key for all types of instruments. It is good for guitar, mandolin, banjo, and it is fine for piano. A diatonic instrument (which has neither flats nor sharps), in the key of C (a marimba for example) will have the root notes of all the chords that are in the key of G. As you can see in the circle graphic above, there are no flats or sharps in the mbira cycle’s chord progression in the key of G.

You can also modulate these chords for any key that you want to play. The karimba could be in A or F. My mbira likes to play in B and E. You might want to transpose these chords to Bb for your clarinet quartet. By integrating the foundational harmonic understanding of the mbira system, we are able to bring mbira music to any instrument.

So far, all the traditional mbira music with which I am familiar does follow the four-phrase model. Not every single mbira song follows this exact harmonic scheme, but I would say that about three quarters of the mbira songs I know do follow it. Most of them do not start in the same place I do, at the “top of the clock,” and that will be something we look at in depth in the next installment of “The System of the Mbira”. The roughly one quarter of mbira songs that do not follow this harmonic scheme precisely still follow it in part – some chords in some of the phrases are replaced by other related chords, but those songs still have the basic flavor of this system. To say it clearly, the chord progression presented here is the ruler by which essentially all traditional mbira music is measured.

I’d like to give you some homework before the next “Mbira System” installment: After studying this post’s four-phrase chord progression and how it sounds, visit YouTube and search for “mbira music” and listen to several of the songs you find. Can you verify that they are all four-phrase music? Can you hear how the four phrases are related to each other? And, do they, or do they not follow the basic chord progression shown above? You may not be able to fully answer this last question, but give it a try. The important things here are to explore music you don’t know and to use your ears and brain as you listen.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades 8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba

8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and Magic

Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and MagicUse of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.