Use of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.

People ask me all the time: “Why do some kalimbas have some upward-bent tines?”

The short answers: it is a design element in many traditional African kalimbas, permitting two interleaved rows of tines, one with shorter tines and the other with longer tines. This not only makes the instrument physically easier to play, but also suggests a host of harmonies and musical motifs that otherwise would be difficult to play.

By the way, I generally call the instruments with two rows of tines “karimba” instead of “kalimba”. (Then there are the mbira, the Sansula, and now the Moon-10 that aren’t exactly karimbas.) The name “karimba” is used by Andrew Tracey to describe the original traditional instrument from 1300 years ago in Africa. Actually, that original instrument consisted of only the 8 lower row tines. Much later, perhaps 800 years ago, a row of shorter, upward-bending tines was added, interleaved with the lower row tines. This design permits you to play all of the ancient songs on the lower tines, and through the higher notes on the upper row, gives you more options for variations and counter melodies… that is, it is true to the ancient while permitting more musical complexity.

The mbira dzavadzimu, the most famous traditional African kalimba, took a different approach: the same original notes from the karimba became the upward-bending short tines, and half a row of much lower and longer tines was interleaved between the upper tines on the left side. In addition, the mbira was expanded by adding more tines on the far left and right.

The two rows of tines is a way of organizing the notes. Instead of having one big complex kalimba, you now have two simpler kalimbas (lower and upper rows) that you can play at the same time. It makes it easier to accompany yourself, or to play multiple lines of music at the same time.

Often, adjacent lower/upper row tines will have a special relationship with one another, with a 5th or an octave interval between them to make for some good playing options. This arrangement makes certain musical moves easy – but they would not be difficult if those notes were more distant or on opposite sides of the kalimba in a planar note layout.

If you interleave long and short tines in this way, the distance between tine tips is increased, making it easier to play the correct tine. Instead of the approximately 1-3 mm accuracy you need in your thumb strokes to play your typical 17-note kalimba, you can get away with a bit of sloppiness: you need only like 3-6 mm accuracy, which frees you to be more energetic and more moving in your playing.

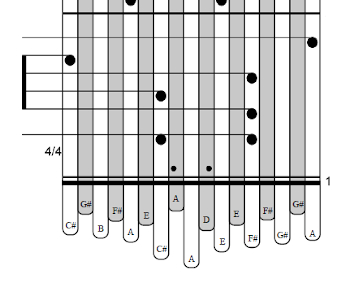

Kalimba Tablature can also be made to reflect the split between lower and upper row tines. My usual convention is to use gray columns to represent the shorter upward-bent tines, and white columns to represent the longer lower row tines. The tine length is indicated at the foot of the tablature, along with the note to which the tine is tuned.

Kalimba Tablature can also be made to reflect the split between lower and upper row tines. My usual convention is to use gray columns to represent the shorter upward-bent tines, and white columns to represent the longer lower row tines. The tine length is indicated at the foot of the tablature, along with the note to which the tine is tuned.

You can see in this little bit of tablature that on the right side, there are two E tines adjacent (the longer one is lower, the shorter one is higher), two F# tines, and two G# tines adjacent to each other. These pairs of adjacent tines make the octave interval. On the left side, you have A to E, B to F# and C# to G# in adjacent tine pairs, making the 5th interval. These intervals – octaves and 5ths – are very important in all music, but this tine arrangement makes these intervals very easy to access on the karimba… which is a good thing, because they are very important in traditional African mbira and karimba music.

This is a very important point: the physical arrangement of the notes on the kalimba has a huge impact on the music that it will easily play. Any music you can play on the African-tuned karimba can also be played on the western-style “flat” kalimbas… but it won’t be easy or natural. Rather, you will have to work at it, while that African-sounding music sort of just drips off of the karimba.

And one more point to think about here: the very shortest tine (that is, the very highest note) on the African tuned Karimba is the high A, right in the middle of the instrument. Kalimbas are usually ergonomically laid out, with longest tines in the center and shorter, higher tines on the far left and right. Think about it – as you hold the kalimba in your hands, rotate your thumbs, moving the thumb nails from the long central tines to the shorter outer tines. It is easy to reach all of those tines. But if you put a very short tine right in the middle of the kalimba, it is not so easy to reach that tine. It is an important note – it is the root note of the African tuned karimba. But think about it – it is like the summit of a mountain. You don’t just hop up to the top of the mountain all the time… but you slowly meander around the instrument, and then when you do go up to that highest note, it is a rare instance. Putting that special note in the middle means that you will play it rarely, as it requires special effort to get there. This makes that highest note special.

There is another playing technique that can help you reach the shortest, highest note right in the karimba center: if you play the upper row right tines with your right index finger, and the lower row tines with your right thumb (another traditional African trick), you will find it is not difficult. By the way, from my observations of their playing, Dumisani (the most famous nyunga player) played using two thumbs and his right index finger, but his daughter Chiwoniso played with just two thumbs. You will find that you can play with more power if you play with just the thumbs, but you will play with more finesss and complexity if you also use your right index finger. A few traditional African instruments are actually played with two thumbs and both index fingers, but I myself find that technique to be a bit awkward. Then again, it is all awkward until you have done for many hours, and then it starts to fall into place.

I should add that not all instruments that have two rows of tines are traditional karimbas. The SaReGaMa Lotus, Freygish, and Air tunings, and the Sansula, the B11 kalimbas, and now the Moon-10 kalimba, all owe a huge debt to the traditional African instruments, but they have moved beyond African music.

Isn’t that a special place to be? Rooted in tradition, yet launching into outer space? And that is the trajectory of the modern kalimba.

Sign up for our newsletter and free resources with your email address:

We pinky promise not to spam you and to only send good stuff.

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades

Assist Paul Tracey Rebuild His House in Pacific Palisades 8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba

8-Note Spiral Kalimba Turned into a Student Karimba Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and Magic

Seek to Infuse Your Musical Moments With Beauty and MagicUse of this website constitutes acceptance of the Privacy Policy and User Agreement. Copyright © 2020 Kalimba Magic. All Rights Reserved.